Healthy musical identities as an aim for music education

In the following paper, we integrate a novel framework, new musical virtuosities, with ideas pertaining to musical identities. Specifically, we propose a new term, healthy musical identity, and suggest that when musical virtuosity is studied through the lens of healthy musical identities, there is a contribution to knowledge since musical virtuosity and musical identity have not yet been discussed together. Furthermore, integrating these two concepts can help researchers and practitioners respond to the needs of contemporary society to fully maximise the potential of universal musicality, facilitating creative development in music in the broadest and fullest sense. This integration of new musical virtuosities and healthy musical identities also interrogates conventional notions of musicality that present barriers to musical engagement.

Music is a fundamental part of human existence, present across the life span from lullabies to funeral songs. It exists ubiquitously in cultures across the world, serving a variety of functions such as facilitating social integration, providing emotional reward, aiding identity construction and much more (MacDonald, 2021; Saarikallio, 2011; Schäfer et al., 2013). Previous work on musical identities (MacDonald et al., 2012) articulates that our identities in music cover numerous constructions, from “I’m a pianist” to those of “I’m a hip-hop lover” or even all the way to notions like “I’m completely tone-deaf”. Beyond our identities in music, music further contributes to building, defining, and expressing our broader identities – our conceptions of who we are, personally, sexually, socially, professionally, politically, and so on. All these musical identities are fundamentally embodied, situated, and dynamic. Thus, the entanglement of music within the entire fabric of our lives is vibrant and in constant flux with numerous types of experience and with our environment (MacDonald & Saarikallio, 2022).

Music is acknowledged as an essential part of humanity in texts that outline principles of music education curricula. For example, in the UK, the national plan for music education (Department of Education, 2011) starts with quotes from Aristotle regarding music as a source of character growth. Similarly, in Finland, the school music curriculum is based on principles that students’ experiences in music education promote not only musical skills but also holistic, social growth suggesting that the personal positive relationship with music creates a foundation for a life-long engagement with music (The Finnish National Agency for Education, 2014).

Proposals for approaching music education in a holistic manner have long been present with appreciation of the related motivational, emotional and participatory rewards (e.g., Wright, 1998). Critical pedagogy approaches to music education have introduced perspectives of social justice and equality, actively bringing the social relevance of music education into the forefront of scientific discussion (Abrahams, 2005; Heard et al., 2023). Ideas have been presented on the requirements that a music teacher faces in terms of how to address the increasingly varying needs of music education students with compassion—with trust, empathy, patience, inclusion, community, and authentic connection (Hendricks, 2018). Various music educational activities such as improvisation have been suggested as a forum for participation, agency and empowerment (Johansen et al., 2019). From the perspective of understanding the essence of what music and music making is, it has been proposed that musical interaction should be viewed as an act that fundamentally reflects our broader humanity and the performance of human relationships (Camlin, 2021, 2022). These considerations date back to the concept of musicking, proposed by Christopher Small (1998), who essentially considered musical behaviour as a forum for articulating and understanding ourselves.

Drawing from these notions, it is logical to argue that music education should focus on musical growth in a holistic manner, appreciating the multiplicity of ways in which music, musicianship, and musical identities manifest in our lives. While this may appear self-evident at the level of principle, we argue that current conceptions do not comprehensively integrate and place in mutual dialogue the knowledge of what it is to learn music, to be musical, and to have musical identities. The holistic ideals are appreciated and developed among the research scholars of music education (Bradley & Hess, 2021; Hendricks, 2023; Hess, 2019a), particularly in the frames of community music and informal practice (e.g., Bartleet, 2023) and to some extent also in relation to institutional practice (e.g., Camlin, 2022). However, addressing musicking as a core aspect of identity is still not at the forefront of how musicality, musical skill, or music learning is conceptualised in education, particularly in the context of formal practice. In this paper we argue that such conceptualisation of music and musicking should be the fundamental starting point of all music education, essentially also including formal institutional practice (see Folkestad, 2006, for more detail on the distinction between formal and informal music making). We therefore particularly focus on music education in this paper as pertaining to the formal teaching of music in institutions (schools, universities, and conservatoires), which also includes many types of conventional private lessons where the focus may be upon the achievement of specific grades and/or technical skills.

This paper presents a humble manifesto concerning what should be at the core of music education as a science and practice. A new framework is proposed for advancing the conceptual grounding of this argument. The humble manifesto of this paper states that the development of healthy musical identities should be acknowledged, appreciated, and researched as a key goal of music education. We argue that musical identities and musical virtuosity issues are inextricably linked, and that this linkage should be explicitly acknowledged. Also, while there has never been an agreed definition of musical virtuosity, general assumptions developed over the course of the 20th century have emphasised technical craft and aspects of musicality such as speed of playing and accuracy of execution. More recently, conceptions of virtuosity have been broadening towards including, for example, various genres, use of technology, and acknowledging the specific virtuosities of individuals with disabilities in order to challenge ableist notions of virtuosity (Devenish & Hope, 2023; Quigley & MacDonald, 2024). Interesting advances in this theorisation involve highlighting the social and communal aspects of virtuosity (Nicols, 2023; Schedel & Thorpe, 2023; MacDonald et al., in press), but the concept of healthy musical identity has not yet been brought in dialogue with this discussion. This paper introduces a proposal for a new conceptualisation of musical virtuosity that includes skills and competencies not previously residing within the repertoire of what might conventionally be seen to be a musical virtuoso in an institutional context. The music educational perspectives described above are enriched with the concept of healthy musical identities and descriptions of how healthy musical identities are embedded in our conceptualisation of musical virtuosity. We further highlight how this relates to openness for participatory perspectives and decolonisation agendas. While “humble” and “manifesto” are not often found together in the same phrase, these words are selected for particular reasons. “Humble” because we are not claiming a fundamentalist trenchant position, as is often the case with manifestos: but rather seek interdisciplinary dialogue to achieve increased conceptual depth and grounding for an issue that has been raised by various scholars, but still would benefit from conceptual sharpening and renewal through integrating new perspectives. We use the term “manifesto” because we believe these are crucial issues that should be of particular focus within music education agendas and practice rather than secondary vague aspirations, as is still often the case. While we emphasise the emerging and evolving nature of these proposals, there are specific implications relating to how music curricula could incorporate explicit reference to the development of healthy musical identities. This would broaden the range of skills targeted in music education to include those outlined below in our new conception of musical virtuosities for healthy musical identities, leading to the implications given at the end of this paper.

What is a healthy musical identity?

Musical identities can be broadly considered to consist of two complementary aspects, identities in music, which refers to our conceptions of our own musicality; and music in identities, the role that music plays in our broader conceptions of ourselves and how we relate to the world (Hargreaves et al., 2002; MacDonald & Saarikallio, 2022). A healthy musical identity can then be considered to reflect adaptive and salutary accounts considering both of these aspects. Considering identities in music, a healthy musical identity implies that an individual is able to pursue musical engagement (e.g., listening, performing, dancing, co-creating) without recourse to overarching feelings of inadequacy stemming from beliefs about being unmusical or not good enough. Such conception of healthy musical identities aligns particularly with the conception of music as a behaviour that affords competence and agency (Stolp et al., 2022a; Wassrin, 2019). In terms of music in identities, healthy musical identities are inherently linked with the broader adaptive functions and rewards that music can offer in relation to identity construction ranging from personal growth to social relatedness (Mas-Herrero et al., 2013; Schäfer et al., 2013). Turning our attention to musical identities as a focus for music education and as an integral part of conceptualising musical skill and virtuosity allows us to take an ecologically valid and holistic approach to the music education of young people and adults across the life span.

Importantly, musicking and musical identities not only pertain to performing and listening, but include talking, writing and thinking about music. It also includes broader psychological and cultural activities such as the formation and maintenance of friendship groups, places to socialise, internet engagement and family relations (MacDonald et al., 2017). Furthermore, while much has been written about the nature of musical identities over the past 20 years, no one has yet developed a theoretical argument about what constitutes a healthy musical identity and how these healthy musical identities intersect with musical skills and engagement.

The focus on healthy musical identities draws attention to how music intersects with wider social and cultural variables and how musical engagement can have a positive impact upon health and well-being (MacDonald et al., 2017). Importantly, it does not imply that someone will be performing music regularly but rather that they will be engaging with music in a way that they will find satisfying and enjoyable. In contrast, there are a range of issues that can be connected with unhealthy musical identities: performance anxiety and stress and psychological issues related to overwork and professional anxieties in particular (Kenny, 2011; Matei & Ginsborg, 2017). There have also been notions of music sometimes fuelling psychologically unhealthy experiences in general (Saarikallio et al., 2015). Our definition of a healthy musical identity thus intrinsically involves perceiving music as a support, resource, opportunity, and strength; not a burden or a source of stress—an approach that aligns with the resource-oriented views of music as a social affordance (DeNora, 2000).

Healthy musical identities are inextricably linked to wider notions of musicking as influentially defined by Small (1998). For example, musicking includes talking about music, performing music (both formally and informally), and attending concerts. In these contexts, a healthy musical identity would include engaging confidently and enjoyably with music at a level to which an individual feels comfortable. These activities include all types of musicking. Contrastingly, while many individuals are interested in music, they lack the confidence or feel they do not have the natural ability to practically engage in music whether that’s learning a musical instrument or having a detailed conversation about musical tastes, preferences and skills. Music education can endeavour to inculcate a healthy musical identity insofar as individuals feel they are able to engage with musical activities to whatever extent satisfies them. Musical identities are thus conceptualised as something we do rather than something we have. Musical identities are performative and are manifested in all the different types of musicking with which we engage. The nature of musical identities is fundamentally dynamic and situationally embedded (MacDonald & Saarikallio, 2022).

When discussing healthy musical identities in relation to learning, emphasis is placed on the psychological aspects of musical learning; for instance to the compelling evidence showing that motivational aspects are crucial for the development of musical skills (McPherson, 2021). Learning to play an instrument involves dedication and focused practise and engagement, while the motivation to engage in this type of purposeful activity is a complex interplay between many factors including perseverance, passion, support, and gratifying experiences of flourishing in music (Olander & Saarikallio, 2022). A relevant distinction here is the difference between internal and external motivation. Externally motivated activities are undertaken in order to achieve an external reward or avoid punishment (Fischer et al., 2019). For example, piano practise to gain approval from a teacher or parent can lead to an individual being externally motivated. If the rewards or punishments are removed, for instance if the lessons stop, or the teacher is no longer present to praise learner development, then the musical engagement may stop as the learner is externally motivated. Conversely, if the learner sees an intrinsic worth in engaging with music, possibly because they enjoy the activities or have a personal goal they wish to achieve then this type of intrinsic motivation may predict continued engagement with music. Intrinsic motivation aligns with the self-determination theory, which argues that intrinsic motivation is supported by the possibilities to fulfil psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2012). Importantly, addressing music education through the lens of healthy musical identities does not undermine the relevance of learning, practising, and skill development, but highlights the intrinsic relatedness of the learning experiences with motivation, gratification, and well-being.

Music educators can be considered to be the valuable and responsible co-creators of supportive structures that facilitate the development of healthy musical identities that holistically relate to the experiences of learning, agency, empowerment, participation, and well-being (Camlin, 2022; Johansen et al., 2019; Stolp et al., 2022b). Yet, there remains significant challenges for music education globally, since huge swathes of individuals around the world feel intensely ‘unmusical’, despite music playing a significant part of their lives (MacDonald, 2021). Importantly, many people report that they are unable to play music, that they are “tone deaf” or that they come from “an unmusical family”. These unmusical assertions are self-perceptions and thus fundamentally linked to notions of musical identity rather than a lack of musical genes, inherited aptitude or musical potential. For example, age is often mentioned as a barrier to participation and many people believe that they are too old to begin to play music. However, there is evidence to suggest this is not the case (Hays & Minichiello, 2005; Jutras, 2011; Li & Southcott, 2015; Varvarigou et al., 2012) and there are numerous examples of older adults engaging in musical activities for the first time. In these contexts, healthy musical identities pertain to how musical skills intersect with other psychological, social and cultural variables that are inextricably linked to musical engagement.

From a pedagogical perspective, healthy musical identities may involve encouraging engagement in a wide variety of creative activities while adopting an inclusive approach to music making. Healthy musical identity has relevance for practical musical engagement, whether that is singing in a community choir, developing a professional performing career, playing guitar with friends or even having the confidence to sing in the shower. Healthy musical identity will predict continued musical engagement, including listening and/or participation, not only in youth, but across the life span (Wan & Schlaug, 2010). The essential argument here is that music education can explicitly target a broader range of activities, including listening, group work, collaborative creative and cross disciplinary activities in order to develop healthy identities. The construction of a healthy musical identity can therefore be supported through a variety of activities such as composing, making music videos, or bringing music in dialogue with drama, visual arts, and dance. In essence, a key challenge for music education is to fully integrate the versatile human universal musicality into music education, practice and research.

Beyond technical mastery: towards improvisatory, creative, social and motivational aspects of virtuosity

Academic and public conceptions of musical virtuosity lie at the heart of what it means to be a musician (Ginsborg, 2018). In order to address musical identities as a central goal for music education we need to critically reflect the concept of musical virtuosity. For hundreds of years the idealist notion of an expert musician—a musical virtuoso—includes someone (very often a male) who has complete technical command of their instrument (Berstien, 2008). This dexterity evolves from decades of learning and solitary daily practise to culminate in someone who plays fast, fluently and accurately (O’Dea, 2008). These musicians become part of a cultural elite, unattainable for most people. While technical command of any instrument must remain part of music education goals, the weight of cultural expectation upon anyone who wishes to develop a serious musical identity related to performance can often inhibit engagement. Icons like Wynton Marsalis or Maria Callas, who embody these notions of virtuosity, are held up as exemplars of what it means to be a musician. These musicians may well exhibit other types of virtuosities that we will discuss in the following paragraphs; however, our contention is that underpinning world famous musical virtuosi are narrow definitions of musical virtuosity. More importantly, these exemplars inhibit many people from engaging with music. This observation in no way challenges the reality that to sing like Maria Callas (or any professional opera singer) or play the trumpet like Wynton Marsalis (or any professional jazz musician) will take years if not decades of practise. Earlier research has suggested that 10,000 hours of practise are required to reach a professional level of technical skill on an instrument (Sloboda, 2004). While subsequent research has challenged the precise amount of time required to reach a “professional” standard of technical excellence, there is no doubt that years of dedicated practise are required to develop the specific required skills. Broadening our definition of musical excellence will encourage future generations to stay engaged with music and develop healthy musical identities.

In this paper, we propose to reconceptualise what musical virtuosity is when approached through the lens of healthy musical identities. From a multidisciplinary perspective, conceptions of virtuosity is a contested issue (MacDonald, 2021). Art education moved beyond purely craft-based notions of virtuosity to include conceptual and multidisciplinary constructions of what it means to be an artist decades ago (Eisner & Day, 2004). Conceptions of musicianship and musical virtuosity are also becoming rapidly more nuanced, and these developments are linked to how healthy musical identities are constructed. Non-Western idioms and non-classical approaches are continually expanding the horizons of what it means to be a musician and this includes a re-imagining and a re-evaluation of what it means to be good at music. Visual arts education and broader aesthetic concepts within art criticism have moved towards including conceptual innovation and issues of wider cultural engagement (Bresler, 2007). Inclusion of a broader repertoire of skills and competencies has become important also for music education, music psychology, and research on musical creativity (Randles & Burnard, 2023). Trends are emerging that emphasise creation instead of reproduction and social skills instead of technical skills, manifested across a range of music research perspectives, from musical performance and participation (Camlin, 2022; MacDonald & Wilson, 2021) all the way to music cognition and music psychology (Clayton et al., 2020; Keller, 2014; Leongómez et al., 2022; van der Steen et al., 2013).

For example, a recognition of improvisation as a fundamental aspect of all music making (not just jazz music) has helped broaden horizons regarding what it means to be musical (MacDonald & Wilson, 2021). Recent developments in sonic arts practices and education highlights the importance of improvisation as sonic arts practice moves into the mainstream of cultural experiences. An early innovator in developing the importance of improvisational practices in music is pioneering improvising vocalist Maggie Nicols. Tonelli (2015) presents an interview with Maggie Nicols and improvising vocalist Phil Minton where they discuss ideas that underpin notions of what is termed “social virtuosity” being important in musical engagement. In this interview improvisational practices that include nonconventional musicking are highlighted as being crucial. Importantly, Nicols links social virtuosity to ethical musical practices that promote inclusivity and also lie at the heart of social virtuosity. Devenish and Hope (2021) develop this idea of social virtuosity to emphasise the distributed nature of creativity and the importance of integrating new developments such as graphic notation into more traditional conventional approaches to musical notation within sonic arts practice and research.

Music education is currently addressing music making not only as reproduction but also as creation, with creative activities and compositional group work and cross-disciplinary working now being much more common than in previous years (Johansen, 2019; Randles & Burnard, 2023). Furthermore, it is not only that creativity is emphasised, but the very definition of creativity is broadening and there are multiple forms of how creativity can be manifested in a music classroom (Clark & Doffman, 2017; Hargreaves et al., 2012) or how it is approached in music and health contexts (Huhtinen-Hildén & Isola, 2019). These accounts point out that musical creativity is not only about creation and integration of musical ideas, but it inherently involves social practices and extra-musical meanings that are being intertwined as elements of musical creation processes.

Participatory perspectives on music making have also been raising the notion of musicking as fundamentally interactive, social, and relational (Camlin, 2022). Music making and music education can be approached as co-creational and compassionate social practice (Hendricks, 2018). Music is by definition a social activity and a significant amount of time during music making is spent in collaboration with others. This collaboration can take many forms such as collaboration of compositional practices and collaboration in performance, rehearsal and preparations (Barrett et al., 2021). These trends in music education research perfectly align with an increasing interest of music cognition and music psychology research to approach musical behaviour and musical skill not as a capacity residing in one person’s head but essentially in the interaction between individuals; in interpersonal alignment, coordination, anticipation, and adaptation of musical expression in ensemble play (Clayton et al., 2020; Keller, 2014; Keller et al., 2014; van der Steen & Keller, 2013). These collaborative activities are a vital part of a musician’s repertoire of skills and a specific virtuosity that may develop via prolonged engagement with music. Thus, collaborative virtuosity may well be a discrete skill that can be developed for musicians across their education and professional career.

The inclusion of social and creative aspects in musical virtuosity also aligns with the evolutionary (Dissanayake, 2008; Leongómez, 2022) and developmental (Trevarthen, 1980; Trondalen, 2019, 2023) perspectives that address the essence of music and its evolutionary significance for humans. According to these accounts the existence of music is grounded in non-verbal communication, intersubjectivity, and social bonding. One could argue that the fundamental aspects of music are its social-interactive, creative, and self-expressive affordances, while the technical skills of music perception and production are secondary manifestations of these primary functions of music. Related argumentation has been proposed for instance by Sciaviao and colleagues (2017) who suggest that there is a shift during infancy from the developmentally earlier protomusicality (of emotionally relevant interaction) to teleomusicality (of exploring and playing with sounds). It has also been proposed that the skills relating to the emotional communication and use of music should be integrated with conceptual understanding of musical competence (Saarikallio, 2018, 2019). These considerations have direct relevance for the practices of music education. Indeed, Young (2016) notes that in early music education in particular there has been a trend towards emphasising a broader understanding of a child’s musical competence in terms of its adaptive functions, motivated by the anthropological and evolutionary perspectives that emphasise the adaptive role of rhythmic synchronisation for prosocial behaviour.

These conceptual trends relate to societal changes. Diversifying music education practice and research is an urgent imperative globally. In the UK for example, those with protected characteristics as defined by the 2010 Equality Act are underrepresented in the artistic field. These include age, disability, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion, sex and sexual orientation. Research that investigates how those working in music can consider artistic strategies and effective ways to accommodate diverse identities can create wider access for those with protected characteristics and help diversify musical practices globally. Person-centred, participatory research approaches that include musicians with protected characteristics and investigate their experiences can help instigate change from an evidence-based perspective. Music educational institutions and cultural organisations are increasingly placing creativity as a key feature of outreach work (MacGlone et al., 2020). A number of artistic approaches to diversifying music education have emerged, where there is potential to tackle issues of politics, gender, race, economics, environment, and community using creative activities (Bartleet & Woolcock, 2023; MacDonald & Wilson, 2020).

However, academic discussions can be controversial and tense with historical hegemonies (politics, gender, genre, etc.) often influencing the debate (Johansen et al., 2019). For example, fixed conventions and views of creativity found in Western classical music can provide the lens through which music is taught, practised and then conceptualised, privileging existing hierarchies (Johansen et al., 2019; Lewis, 1996). In Scotland, over 50% of musicians from an ethnic minority background (we use this term to refer to all ethnic groups except White British individuals) felt that their ethnicity was a barrier to career progression (Creative Scotland, 2017). Lack of understanding about the cultural themes of artists’ work was the most common reason given (Creative Scotland, 2017). Therefore, investigating ways forward is an important priority post-COVID. For example, ethnic minority communities have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and evidence for the exclusion of those with protected characteristics from academic discourse and practice in music has also been outlined (Kirby, 2020; Mwamba & Johansen, 2021). Issues of intersectionality therefore remain a research priority (Hess, 2019b).

With these issues in mind, Lewis (2020) proposes “8 difficult steps” towards decolonising contemporary music. These suggestions can clearly contribute to discussion, action and evaluation for many types of musical engagement and include: moving beyond friendship groups to reach and include new communities; explicitly prioritising diversity in all educational contexts via research, commissioning and hiring strategies and policies; emphasising internationalisation by working on international collaborations which inform and support each other; encouraging media discussions of decolonisation and publicly articulating plans for how practices will be decolonised. These measures will positively affect changes in musical identities, develop our ideas of what musical virtuosities are, and help achieve a broadening of cultural perspectives and practices within institutions and beyond.

A framework of New Musical Virtuosities for Healthy Musical Identities

The aforementioned trends in music research suggest that a new understanding of musical virtuosity is emerging and needed. Drawn from these considerations, and approaching musical virtuosity particularly through the lens of healthy musical identities, we propose a conceptual framework of New Musical Virtuosities. This framework is grounded on the idea that musical virtuosity is fundamentally about a healthy musical identity, not reliant on a particular skill but rather on the holistic presence of what it means to engage in music, be musical, and have a musical identity. The framework is influenced by prior literature on musical identities and the participatory and creative accounts that have begun to broaden the understanding of what it means to be a virtuoso in music. Below we present the contents of the framework in detail, and in dialogue with concrete examples.

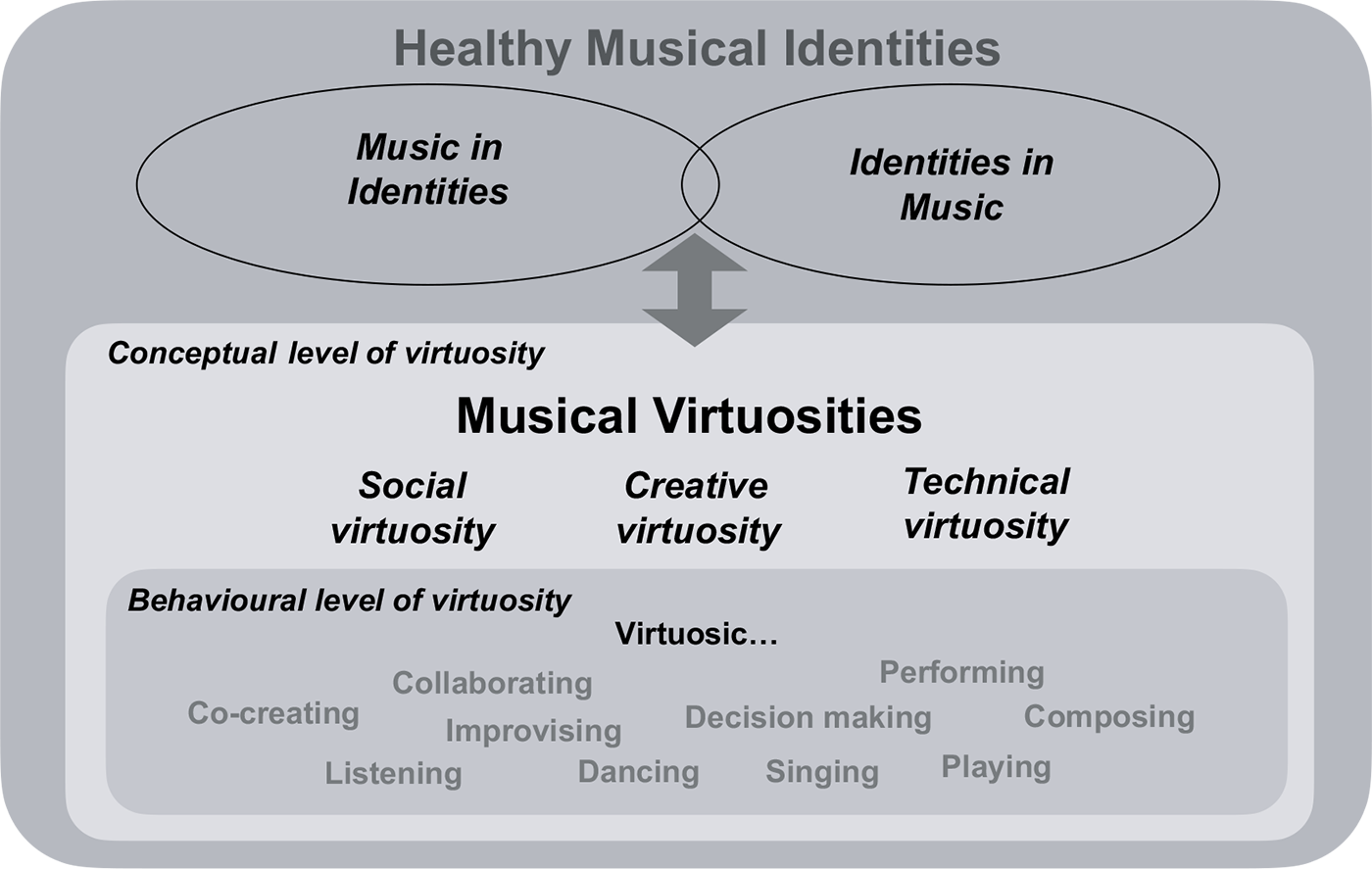

The framework for New Musical Virtuosities for Healthy Musical Identities is illustrated in Figure 1. At the core of the framework is a proposition to conceptually reconsider the essence of what musical virtuosity is: It is not only technical but also social and creative by nature. From this it follows that on the behavioural level we can observe a wide range of visible manifestations of such virtuosity, including creative and collaborative acts of musicking. All of these behaviours and aspects of virtuosity are mutually influential and important for the creation of musical identities towards healthy musical identities.

The three aspects of musical virtuosity—social virtuosity, creative virtuosity, and technical virtuosity—can be conceptualised as three discrete terms. However, it is important to note that there may be overlap. Creative virtuosity can include skills that are involved in interacting and collaborating creatively, producing new work and generating new ideas. Of course, creativity in itself is an ambiguous term and there is a considerable amount of literature and research investigating the social and psychological foundations of creativity (e.g. Csikszentmihalyi, 2014; Kaufman, 2016). For the purposes of this paper, we take a broad definition of creativity and suggest that it pertains to all activities involved in the generation and performance of new artistic work. Historical accounts of creativity in Western music are dominated by singular individuals (usually male) and these accounts address creativity as an internal quality that some individuals have more of and others less. However, the reality of music making is that it predominantly occurs in groups. In this respect, creativity can also be viewed as a social quality and music making is an excellent example of distributed creativity. Thus, concerning the framework of new virtuosities for healthy musical identities, it is important to also emphasise the distributed nature of creativity (Clark & Doffman, 2018).

When we move to social virtuosity the focus shifts more on the social skills, interpersonal communication, group interactions, and specific strategies and knowledge that facilitate effective communication across different social contexts. Listening skills, sensitive nonverbal communication skills, or empathic interactions facilitating an enhanced understanding of others, may all be seen as components of social virtuosity. Yet, it should be clear that while creative virtuosity and social virtuosity perhaps emphasise different specific behaviours and outcomes, there may be overlap between what could be termed socially virtuosic and creatively virtuosic. Finally, technical virtuosity includes skills that can be considered to be conventionally required by an elite musician, including for example advanced motor coordination, precise musical perception, rhythmic awareness, melodic awareness and reading abilities. Yet, while a single behaviour of playing an instrument can be defined as what one might call technical virtuosity of a single individual, the act of using these technical skills in playing or improvising together in a group is also fundamentally an act of social and creative virtuosity (MacDonald & Wilson, 2020; Siljamäki, 2022; van der Steen & Keller, 2013). From this perspective there is an inherent overlap between all of the three concepts.

At the behavioural level we can observe a range of specific activities involved in the integration of social, creative, and technical virtuosities. For example, in order to sing virtuosically, not only must an individual have accurate listening skills, very sensitive control of their vocal cords, understanding of timbre tonality, and how emotional expression can be imbued by the control of various muscles and anatomical features of the body, but they must also understand aspects of the context in which they are singing, the audience, who are they performing with, how to interact with other musicians who are part of the group and/or how to navigate singing with a conductor. These types of behavioural level acts and skills, whether it is singing, playing the drums, or composing, involve an integration of the three broad categories of social, creative and technical virtuosity.

Another good example of a behaviour that illustrates the integration of social, creative, and technical aspects of virtuosity is the capacity to make decisions. A considerable amount of time is spent by musicians in making decisions. When to start, when to stop, how loud to play, what timbral qualities to infuse into particular notes and patterns. Indeed one theory of improvisation suggests decision making is a primary and defining aspect of improvisation and that improvisation is at the heart of music making (MacDonald & Wilson, 2021). A related model called, The Adaptation an Anticipation Model (Keller, 2014; van der Steen & Keller, 2013) zooms into the temporal sensorimotor coordination between ensemble musicians, emphasising adaptation and anticipation as critical skills of music making. These types of decisions also expand to compositional, rehearsal and preparatory activities and involve a range of social and creative processes. Thus, decision making is an example of a discrete skill that musicians can develop and should take its place among contemporary virtuosities.

Musical participation is also not only concerned with playing but also listening. Indeed, working in ensembles involves sensitive listening skills, whether that is in a classical orchestra, a jazz band or a rock band. Musicians need to be keenly aware of what others are playing and make musical decisions based upon these listening practices. Music listening is perhaps typically considered a skill and a type of expertise that particularly relates to informal musicking of non-musicians (e.g., Lamont & Greasley, 2011), but the skill of listening is actually needed and will develop during both formal and informal, both solitary and shared, musical engagement. Listening virtuosity can be considered as a discrete type of skill that can be developed to a high level in an experienced musician.

In summary, the proposed framework introduces the term “new virtuosities” and proposes that musical virtuosity includes three interrelated categories that underpin what it means to be virtuosic and also lie at the heart of discrete behavioural manifestations of virtuosities such as singing, composing, collaborating, dancing, performing, etc. All these activities involve social, creative, and technical aspects of virtuosity and having a broad definition of musical virtuosity can help inculcate what we have termed healthy musical identities. These features contribute to defining music as social, interactive, collaborative, and cultural and offer a framework for how the development of a healthy musical identity can be supported by and integrated into music educational practice. The framework of new musical virtuosities for healthy musical identities grows from recent trends of music research with creative, social, and participatory perspectives achieving increasing attention, yet it takes this discussion one step further by integrating these perspectives into the very definition of musical virtuosity. Fundamental to the proposed framework are not its exact components: further empirical work is needed for their refinement. Instead, at the heart of the framework is a shift of perspective in conceptualising what it means to be musically virtuosic; the new virtuoso holds a broad variety of social, creative, and technical skills that fundamentally support the construction of healthy musical identities for us all.

Implications of a new virtuosity and healthy musical identity framework for research and practice

While the importance of music to holistic growth and social behaviour has been acknowledged and appreciated across a wide range of research literature in music and music education, participatory and creative aspects have not previously been conceptually emphasised as directly being musical skills and competences (Hargreaves, 1996; Stefani, 1987). This lack of emphasis has kept these important perspectives on the sidelines of music education, treated as additional rewards, secondary outputs, or transfer effects of musical practice. Conceptualising social and creative aspects of musicking as the core aspects of musical virtuosity changes this picture. Aspects of protomusicality (Sciaviao et al., 2017), non-verbal communication (Leongómez, 2022), performance of relationships (Camlin, 2021) and emotional competences (Saarikallio, 2018) no longer serve as only positive impacts but as defining skills and competencies of virtuosic musicking. Healthy musical identities become highlighted as the fundamental aim of research and practice, and the ideal of a musical virtuoso expands towards and leans into an increasingly holistic, dialogical, and inclusive one.

The new framework resonates well with recent developments in music, health and well-being perspectives where there has been a huge growth of interest in how music engagement contributes to health (Fancourt & Finn, 2019; MacDonald et al., 2012). Researchers and practitioners working with the young have identified numerous ways in which music can support students’ social-emotional development and identity construction (McFerran et al., 2019). It is important to consider health promotion and musical learning as essentially dialogical, and mutually inclusive ones and not separate (or even contradictory) areas of experience. The framework of new musical virtuosities for healthy musical identities aligns with learner-centred approaches to education (Huhtinen-Hildén & Pitt, 2018) and offers possibilities for further dialogue across perspectives of education and health promotion.

Shifting the conceptualisation of musical virtuosity towards a greater emphasis on social and creative aspects has direct implications for the objectives and practices of music education (MacDonald et al., in press). The way musical skill and virtuosity is defined becomes visible in how music lessons are structured, activities appreciated, and assessments conducted. One practical example of a pedagogical innovation for creating spaces for collaborative learning in music is a project called the Music Tower, developed by Mikko Myllykoski (2019). Music Tower is a technology-based learning environment, particularly designed to support student-centred, collaborative, and creative musicking. Other examples of the practical implications of the preceding discussion regarding healthy musical identities and new virtuosities may include class activities that incorporate a broader range of creative skills and challenges. This resonates well with increasing interest of music educators in addressing a pluralistic view of music as an act of multimodal group creativity (Randles & Burnard, 2023). Examples of this could include setting creative projects and encouraging students to engage in multidisciplinary activities incorporating movement and music where the output is not specified. Projects could involve students creating a film with dancers, or musicians or students creating a new board game that involves musical instructions and performances (MacDonald & Wilson, 2021). The key point here is to give students the opportunity to engage with a broad range of critical, creative and social skills encompassing what we call new virtuosities and emphasising that there is no correct answer may help inculcate healthy musical identities. Such developments advocate the inclusion of creativity in the contemporary conceptualisations of musical skill and virtuosity (Hargreaves et al., 2012).

New ways of conceptualising virtuosity, skill, and competence also have direct implications on how to assess, grade and mark students’ work. Some challenges may emerge in assessing the new virtuosities, since there exists a multitude of perceptions among teachers, for instance, of how to define creativity: it can be manifested in a learning style of a student, in a type of a group process of musical creation, or in the originality of the end result (Odena & Welch, 2012). This raises the question to what extent precise marking schemes are beneficial for developing not only students’ skills, but also healthy musical identities. Perhaps grading schemes that are less intricate (e.g., pass, fail, merit) and encourage engagement and self-directed learning are more beneficial to developing healthy music identities than awarding students a precise mark out of 100 for numerous individual assessments. Regardless, assessment schemes should not include only one type of virtuosity but be inclusive of the holistic conceptualisation of musical virtuosity. Possible avenues in this area also consist of integration of students’ perceptions and peer-assessment procedures. Such accounts fluently align with the recent participatory models of research, which emphasize the need for the research participants to be included in all aspects of the research process from planning through to dissemination (MacGlone et al., 2022).

Indeed, participatory models of research can also be at the heart of the developments of further refining our understanding of the proposed new virtuosities. Ilari (2020) argues that there is a need for a closer dialogue between music educators and psychology researchers: psychological interventions demonstrate that music education contributes to many areas of child development that are relevant to healthy musical identities, yet these studies often lack qualitative insight on how the practice of music education can be developed for reaching these outcomes (Ilari and Habibi, 2023). Furthermore, Varner (2018) argues that music educators and parents are still largely unaware of the distinct contributions that music has been shown to have on improved emotional, intellectual, and social areas of cognition. One solution is that music education would embrace participatory models of research to include research participants in all stages of the research process. These new models of research seek to challenge the hegemonic power dynamics between researcher and participant, and this is particularly important within music education research as we seek to develop ecologically valid research that responds to contemporary priorities (MacGlone et al., 2022). For example, in many cases the voice of the participant, very often young people, can only be accessed via conventional focus groups and interview research yet the design of an experiment crucially influences the type of data analysis and conclusion drawn. Including participants in all stages of the research process may help generate ecologically valid results and also contribute to the developing healthy music identities of everyone involved in musical engagement. Music education research would benefit from including research participants, possibly as “lay researchers”, to provide insights and interpretations not possible for more experienced researchers, thus strengthening the relevance of findings.

There are numerous modes of participatory research offering varying types of collaboration between academic researchers and outside communities. This includes ad hoc collaboration where researchers informally collaborate with stakeholders through to full institutional commitment and collaboration where research participants may be on advisory committees and co-authors on research outputs (McLean et al., 1993). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, which also challenges the conventional relationship between researcher and participants moving from research “on” to research “with” communities (Hacker, 2013). Laes and Westerlund (2018) investigated student teachers’ perceptions of teaching, proposing that music education needs to expand ideas of professionalism and how expertise is conceptualised. These new approaches to research can help us understand how new virtuosities function with the broader landscape of music participants and can help inculcate more healthy musical identities.

The new conceptualisation of musical virtuosity may also provide fruitful perspectives to the wider accessibility and decolonisation of music education. Arguments presented above emphasise the importance of decolonising music education (Lewis, 2022) so that all musical genres, types and practices are afforded equivalent status, with an emphasis on racial, gender and social equality. These developments have also necessitated a re-imagining of what music virtuosities may be. This links with broader discussions of ownership and access, suggesting that it is crucial to offer a broad access to music education, for old and young, to those with and without technical mastery, and advocate for inclusive approaches to musical engagement.

Broadening our definition of virtuosity allows a renegotiation of the hegemonic power hierarchies at play with music and indeed the wider cultural industries (Lewis, 2022). Collaboration can be viewed as a fundamental aspect of not only musical engagement but all creative activities (Barrett et al., 2021). If we can re-imagine what virtuosity may entail in terms of collaboration, we may be able to open the concept of virtuosity even beyond the context of musicking. Musicians, artists, dancers, writers, filmmakers are all expected to collaborate and to be truly virtuosic within a contemporary context that necessitates an advanced ability to collaborate in social creative contexts. Considering broader definitions of virtuosity facilitates a comparison between different disciplines in terms of what it means to be virtuosic. The proposed framework therefore is not a fixed model, but rather a change in perspective, an inclusive invitation to negotiate and grow together.

Recommendations

The preceding paragraphs suggest that developing healthy musical identities should lie at the heart of music education practice and that the new conceptualisation of virtuosity can help us achieve these goals. As a conclusion of the paper, we return to the humble manifesto and propose the following key points:

- Music education should encourage the development of healthy musical identities. Musical identities are embodied, situated, and dynamic and include both listening to music and practical musical engagement. The development of healthy musical identities as a goal for music education will facilitate engagement with music across the life span.

- Music education should embrace new musical virtuosities. New musical virtuosities include a range of skills and competences that move beyond the traditional craft-based approaches to teaching music. Skills such as collaborating, group work, creative engagement, listening and the wider socio/relational aspect of music making are central to new musical virtuosities.

- Music education should integrate participatory models of research and incorporate decolonisation agendas. Including research participants and other “stakeholders” in all stages of the research process will significantly enhance the ecological reliability and validity of research findings and enhance their impact.

The humble manifesto presented in the current paper is motivated by a desire to offer music education a vibrant and holistic viewpoint to what music and music education is and how the discipline can be renewed through conceptual renegotiation. The new virtuosities for healthy musical identities framework encourages interdisciplinary dialogue and participatory knowledge creation, but essentially highlights music education as a discipline that lies at the very heart of humanity.

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 101045747) and from the Research Council of Finland (grant no. 346210). Views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

References

- Barrett, M. S., Creech, A. & Katie, Z. (2021). Creative collaboration and collaborative creativity: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713445

- Bartleet, B. L. (2003). A conceptual framework for understanding and articulating the social impact of community music. International Journal of Community Music, 16(1), 31–49.

- Bernstein, S. (1998). Virtuosity of the nineteenth century: Performing music and language in Heine, Liszt, and Baudelaire. Stanford University Press.

- Bradley, D. & Hess, J. (2021). Trauma and resilience in music education: Haunted melodies. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003124207

- Bresler, L. (2007). International handbook of research in arts education. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Camlin, D. A. (2021), Recovering our humanity – what’s love (and music) got to do with it? In K. Hendricks & J. Boyce-Tillman (Eds.), Authentic connection: Music, spirituality, and wellbeing (pp. 293–312). Peter Lang.

- Camlin, D. A. (2022), Encounters with participatory music In M. Dogantan-Dack (Ed.), The chamber musician in the twenty-first century (pp. 43–7). MDPI Books.

- Clarke, E. F. & Doffman, M. (2017) Distributed creativity: Collaboration and improvisation in contemporary music. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199355914.001.0001

- Clayton, M.,Jakubowski, K., Eerola, T., Keller, P. E., Camurri, A., Volpe, G. & Alborno, P. (2020). Interpersonal entrainment in music performance: Theory, method, and model. Music Perception, 38(2), 136–194. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2020.38.2.136

- Creative Scotland. (2017). Understanding diversity in the arts. https://www.creativescotland.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/42920/Arts-and-Diversity-Survey-Summary.pdf

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Society, culture, and person: A systems view of creativity. In M. Csikszentmihaly, The systems model of creativity. The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pp. 47–61). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9085-7_4

- DeNora, T. (2000). Music in everyday life. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489433

- Department of Education. (2011). The importance of music: A national plan for music education.

- The Finnish National Agency for Education. (2014). Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet [Curriculum foundations for the comprehensive school]. https://www.oph.fi/fi/koulutus-ja-tutkinnot/perusopetuksen-opetussuunnitelman-perusteet

- Devenish, L., & Hope, C. (Eds.). (2023). Contemporary musical virtuosities (1st. ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003307969

- Devenish, L. & Hope, C. (2021). The new virtuosity: A manifesto for contemporary sonic practice. Tempo, 75(298), 87–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0040298221000437

- Dissanayake, E. (2008). The arts after Darwin: Does art have an original and adaptive function? In K. Zijlmans & W. van Damme (Eds.), World art studies: Exploring concepts and approaches (pp. 241–261). Amsterdam: Valiz.

- Eisner, E. W. & Day, M. D. (2004). Handbook of research and policy in art education. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Fischer. C, Malycha, C. P., & Schafmann, E. (2019) The influence of intrinsic motivation and synergistic extrinsic motivators on creativity and innovation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00137

- Folkestad, G. (2006). Formal and informal learning situations or practices vs formal and informal ways of learning. British Journal of Music Education, 23(2), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051706006887

- Ginsborg, J. (2018). “The brilliance of perfection” or “pointless finish”? What virtuosity means to musicians. Musicae Scientiae, 22(4), 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864918776351

- Greasley, A. E. & Lamont, A. (2011). Exploring engagement with music in everyday life using experience sampling methodology. Musicae Scientiae, 15(1), 45–71.

- Hays, T. & Minichiello, V. (2005). The meaning of music in the lives of older people: a qualitative study. Psychology of Music, 33(4), 437–451.

- Hargreaves, D. J., Miell, D. & MacDonald, R. A. R. (Eds). (2012). Musical imaginations. Oxford University Press.

- Heard, E., Bartleet B. L. & Woolcock, G. (2023). Exploring the role of place-based arts initiatives in addressing social inequity in Australia: A systematic review. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 550–572. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.257

- Hendricks, K. S. (2018). Compassionate music teaching: A framework for motivation and engagement in the 21st century. Rowman & Littlefield Press.

- Hendricks, K. S. (Ed.). (2023). The Oxford handbook of care in music education. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197611654.001.0001

- Higgins, L. (2020), Note 57: Hospitable approaches to community music scholarship. International Journal of Community Music, 13(3), 223–33.

- Huhtinen-Hildén, L. & Pitt, J. (2018). Taking a learner-centred approach to music education – pedagogical pathways. Routledge.

- Huhtinen-Hildén, L. & Isola, A.-M. (2019). Reconstructing life narratives through creativity in social work. Cogent Social Sciences, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1606974

- Hess, J. (2019a). Music education for social change: Constructing an activist music education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429452000

- Hess, J. (2019b). Singing our own song: Navigating identity politics through activism in music. Research Studies in Music Education, 41(1), 61–80.

- Ilari, B. & Habibi, A., (2023). The musician-nonmusician conundrum and developmental music research. In E. H. Margulis, P. Loui & D. Loughridge (Eds.), The science-music borderlands: Reckoning with the past and imagining the future. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/14186.001.0001

- Johansen, G. G., Holdhus, K., Larsson, C. & MacGlone, U. M. (Eds). (2019). Expanding the space for improvisation pedagogy in music. Routledge.

- Johansen, G. G. (2019). Seven steps to heaven? An epistemological exploration of learning in jazz improvisation, from the perspective of expansive learning and horizontal development. In G.G. Johansen, K. Holdhus, C. Larsson & U. M. MacGlone (Eds), Expanding the space for improvisation pedagogy in music (pp. 245–260). Routledge.

- Johansen, G. G., Holdhus, K., Larsson, C. & MacGlone, U. M. (2019). Expanding the space for improvisation pedagogy in music – an introduction. In G. G. Johansen, K. Holdhus, C. Larsson, & U. M. MacGlone (Eds.), Expanding the space for improvisation pedagogy in music: a transdisciplinary approach (pp. 1–9). Routledge.

- Jutras, P. J. (2011). The benefits of new horizons band participation as self-reported by selected New Horizons band members. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 187, 65–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41162324

- Kirby, T. (2020). Evidence mounts on the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(6), 547–548.

- Kaufman, J. C. (2016). Creativity 101 (2nd edition). Springer Publishing Company.

- Keller, P. (2014). Ensemble performance: Interpersonal alignment of musical expression. In D. Fabian, R. Timmers & E. Schubert (Eds), Expressiveness in music performance: Empirical approaches across styles and cultures. Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199659647.003.0015

- Keller, P., November, G. & Hove, M. J. (2014). Rhythm in joint action: Psychological and neurophysiological mechanisms for real-time interpersonal coordination. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 369(1658). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0394

- Kenny, D. T. (2011) The psychology of music performance anxiety. Oxford University Press.

- Laes, T. & Westerlund, H. (2018), Performing disability in music teacher education: Moving beyond inclusion through expanded professionalism, International Journal of Music Education, 36(1), 34–46.

- Legislation.gov.uk. (2016). Equality Act 2010. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

- Leongómez, J. D., Havlíček, J., & Roberts, S. C. (2022). Musicality in human vocal communication: An evolutionary perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 377(1841), 20200391. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0391

- Lewis, G. E. (2022). New music decolonization in eight difficult steps. VAN Outernational. https://www.van-outernational.com/lewis-en (English), https://www.van-outernational.com/lewis (German), https://www.van-outernational.com/lewis-fr (French).

- Lewis, G. E. (1996). Improvised music after 1950: Afrological and Eurological perspectives. Black Music Research Journal, 91–122.

- Lewis G. E. (2020). “8 difficult steps”. Curating diversity in Europe – decolonising contemporary music conference. https://www.van-outernational.com/lewis-en/

- Li, S. & Southcott, J. (2015). The meaning of learning piano keyboard in the lives of older Chinese people. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 34, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2014.999361

- Lindsey, E. & McGuinness, L. (1998). Significant elements of community involvement in participatory action research: Evidence from a community project. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(5), 1106–1114.

- MacDonald, R. (2021). The social functions of music: Communication, wellbeing, art, ritual, identity and social networks (C-WARIS). In A. Creech, D. A. Hodges, & S. Hallam (Eds.), Routledge international handbook of music psychology in education and the community (pp. 5–20). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429295362-3

- MacDonald, R., Birrell, R., Burke, R., De Nora, T. & Sappho, M. (in press). The theatre of home: Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra and new directions in creativity. Oxford University Press.

- MacDonald, R. A. R, Kreutz, G. & Mitchell, L. A. (Eds.). (2012). Music, health and wellbeing. Oxford University Press.

- MacDonald, R. A. R, Miell, D. & Hargreaves, D. J. (Eds.). (2017). The Oxford handbook of musical identities. Oxford University Press.

- MacDonald, R. A. R. & Birrell, R. (2020). Flattening the curve: Glasgow Improvisers Orchestra’s use of virtual improvising to maintain community during COVID-19 pandemic. Critical Studies in Improvisation, 14(2–3). https://www.criticalimprov.com/index.php/csieci/article/view/6384

- MacDonald, R. A. R, Burke, R. L., De Nora, T., Sappho Donohue, M. & Birrell, R. (2021). Our virtual tribe: Sustaining and enhancing community via online music improvisation. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.623640

- MacDonald, R. & Saarikallio, S. (2022) Musical identities in action: Embodied, situated, and dynamic. Musicae Scientiae, 26(4), 729–745.

- MacDonald, R. & Wilson, G. (2020). The art of becoming: How group improvisation works. Oxford University Press.

- MacGlone, U., Wilson, G. B., Vamvakaris, J., Brown, K., McEwan, M. & MacDonald R. A. R. (2022). Exploring approaches to community music delivery by practitioners with and without additional support needs: A qualitative study. International Journal of Community Music, 15(3), 385–403.

- Mas-Herrero, E., Marco-Pallares, J., Lorenzo-Seva, U., Zatorre, R. J. & Rodriguez-Fornells, A. (2013). Barcelona music reward questionnaire (BMRQ) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t31533-000

- Matei, R. & Ginsborg, J. (2017). Music performance anxiety in classical musicians – what we know about what works. British Journal of Psychology Int., 14(2), 33–35. https://doi.org/10.1192/s2056474000001744.

- Myllykoski, M. (2019). Edutorni, 2019 [Website]. http://www.edutorni.fi/esittely/

- Mwamba, C. & Johansen, G. G. (2021) Everyone’s music? Explorations of the democratic ideal in jazz and improvised music. Utdanningsforskning i musikk – skriftserie fra CERM (Centre for Educational Research in Music), 3. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2826181

- McFerran, K. Derrington, P. & Saarikallio, S. (Eds.). (2019). Handbook of music, adolescents and wellbeing. Oxford University Press.

- McPherson, G. E. (2021). Redefining the teaching of musical performance. Visions of Research in Music Education, 16(15).

- McLean, E., Petras, P. & Porpora, D. V. (1993). Participatory research: Three models and an analysis. The American Sociologist, 24, 107–126.

- O’Dea, J. (2000). Virtue or virtuosity? Explorations in the ethics of musical performance. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Odena, O. & Welch, G. (2012). Teachers’ perceptions of creativity. In O. Odena (Ed.), Musical creativity: Insights from music education research (pp. 29–48). Ashgate.

- Olander, K. & Saarikallio, S. (2022). Experiences of grit and flourishing in Finnish comprehensive schools offering long-term support to instrument studies: Building a new model of positive music education and grit. Finnish Journal of Music Education, 25(2), 87–109.

- Quigley, H. & MacDonald, R. (2024). A qualitative investigation of a virtual community music and music therapy intervention: A Scottish–American collaboration. Musicae Scientiae, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10298649241227615

- Randles, C. & Burnard, P. (2023) The Routledge companion to creativities in music education. Routledge.

- Saarikallio, S., McFerran, K. & Gold, C. (2015). Development and validation of the Healthy-Unhealthy Music Scale (HUMS). Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 210–217.

- Saarikallio. S. (2011). Cross-cultural approaches to music and health. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health and wellbeing. Oxford University Press.

- Saarikallio, S. (2018). At the heart of musical competence: Music as affective awareness. In E. K. Orman (Ed.), Proceedings of the 27th international pre-conference seminar of the ISME commission on research in music education, Dubai, July 8–13, 2018 (pp. 146–155).

- Saarikallio, S. (2019). Access-awareness-agency (AAA) model of music-based social-emotional competence (MuSEC). Music and Science, 2, 1–16.

- Schiavio, A., van der Schyff, D., Kruse-Weber, S. & Timmers, R. (2017). When the sound becomes the goal. 4E cognition and teleomusicality in early infancy. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1585. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01585

- Schäfer, T., Sedlmeier, P., Städtler, C. & Huron D. (2013). The psychological functions of music listening. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(4), 511. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00511

- Siljamäki, E., (2022). Free improvisation in choral settings: An ecological perspective. Research Studies in Music Education, 44(1), 234–256.

- Sloboda. J. (2005). Exploring the musical mind: Cognition, emotion, ability, function. Oxford University Press.

- Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The meanings of performing and listening. Wesleyan University Press.

- Stolp, E., Moate, J., Saarikallio, S., Pakarinen, E. & Lerkkanen, M.-K. (2022a). Exploring agency and entrainment in joint music-making through the reported experiences of students and teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 964286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.964286

- Stolp, E., Moate, J., Saarikallio, S., Pakarinen, E. & Lerkkanen, M.-K. (2022b). Teacher beliefs about student agency in whole-class playing. Music Education Research, 24(4), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2022.2098264

- Tonelli, C. (2016). Social virtuosity and the improvising voice; Phil Minton & Maggie Nicols interviewed by Chris Tonelli. Critical Studies in Improvisation / Études critiques en improvisation, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.21083/csieci.v10i2.3212

- Trevarthen, C. (1980). The foundations of intersubjectivity: Development of interpersonal and cooperative understanding in infants. The social foundations of language and thought: Essays in honor of Jerome S. Bruner (pp. 316–342).

- Trondalen, G. (2019). Musical intersubjectivity. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 65, 101589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2019.101589

- van der Steen, M. C. & Keller, P. E. (2013). The adaptation and anticipation model (ADAM) of sensorimotor synchronization. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10(7), 253. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00253

- Varner, E. (2019). Holistic development and music education: Research for educators and community stakeholders. General Music Today, 32(2), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048371318798829

- Varvarigou, M., Hallam, S., Creech, A. & McQueen, H. (2012). Benefits experienced by older people in group music-making activities. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 3, 183–198.

- Wan & Schlaug. (2010). Making music as a tool for promoting brain plasticity across the life span. The Neuroscientist, 16(5), 566–577.

- Wassrin, M. (2019). A broadened approach towards musical improvisation as a foundation for very young children’s agency. In. G. G. Johansen, K. Holdus, C. Larsson & U. M. MacGlone (Eds.), Expanding the space for improvisation pedagogy in music (pp. 33–50). Routledge.

- Wright, R. (1996). A holistic approach to music education. British Journal of Music Education, 15(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051700003776