Introduction

There have been several studies on teacher identity, and music teacher identity in particular, using various methods of investigation. Based on findings from a study on professional identities of music teachers within Norwegian municipal schools of music and performing arts1 (see also Jordhus-Lier, 2018), I argue that using discourse analysis to understand professional music teacher identity is fruitful. It offers an understanding of the field wherein identities are constructed, and of the connection between the field (structure) and the people working within it (agency). It can reveal how meaning is being constructed, which is crucial if taken-for-granted knowledge is to be challenged and potential struggles in the field are to be discovered. A discourse analysis of professional teacher identities opens up for describing the complexity and power relations of a field, and how and why identities are negotiated. Several previous studies (Angelo & Kalsnes, 2014; Bernard, 2005; Bouij, 1998; Broman-Kananen, 2009; Roberts, 2004; Stephens, 1995) have tended to focus on music teacher identities as primarily centred around a teacher–musician dichotomy. I assert that discourse analysis could reveal a richer complexity in music teachers’ identities.

There is an increasing importance placed on breadth, versatility and social inclusion as key tenets of the Norwegian school of music and arts, while depth and specialisation continue to be highlighted in various policy documents and in the practice of many teachers (Berge et al., 2019; Ellefsen & Karlsen, 2019; Jordhus-Lier, 2018; Karlsen & Nielsen, 2020; Norsk kulturskoleråd, 2016). As a result, the school and its teachers are negotiating various and diverse tasks in a field that contains tension. Music teachers are often specialists and have comprehensive training in their speciality, but, simultaneously, they must relate to the school’s mission, including the commitment to social inclusion and breadth. In my research, I used discourse analysis to explore the professional identities of those teachers, a method which helped me reveal how these issues were handled by the school and its teachers.

In this research, I built on a social science-related discourse analysis where discourse is perceived as a totality of language and practices, with the overarching theoretical and analytical framework being Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse theory (Laclau, 1990; Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). I also built on theories of professions (Abbott, 1988; Freidson, 2001; Molander & Terum, 2008), which added a frame for discussing what it means for an occupational group to be a profession, and provided access to a better understanding of the tensions created. Methods and theory are closely connected in discourse analysis, but Laclau and Mouffe’s (2001) discourse theory provides few methodological guidelines. When carrying out a discourse analysis based on Laclau and Mouffe, a brief outline of their theory has to be given, as well as a presentation and justification of how it was used methodologically. In this article, I will thus describe some concepts from Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse theory, and how I used them in my research. I will also account for why and how theories of professions were connected to the discourse theoretical framework. The aim of this article is not to discuss the results of the research, but in order to be able to discuss the relevance of using discourse analysis to study professional music teacher identity, I will provide a short overview of the analytical findings.

Relevant Nordic research on teacher identity, professionalism and discursive structures

Of relevance to the discussion about using discourse analysis to understand professional music teacher identity is research on (music) teacher identity, professionalism and discursive structures within the (music) educational field. Because my research is performed in a Norwegian context, research within the Nordic educational field is most relevant. Angelo’s (2012) thesis about philosophies of work in instrumental music education is a thematic narrative analysis of three instrumental teachers’ stories, and it addresses their professional understandings of their work, mandate and expertise: their “philosophies of work”. Angelo (2012) did not perform a discourse analysis, but the main aspects of “philosophies of work” are, as she understands it, power, identity and knowledge. These elements are relevant to discussions on professional music teacher identity, and they are central in my research. However, in order to contextualise and get a greater understanding of the field wherein identities are constructed, I chose as my field of study the school of music and arts and the methodology discourse analysis.

Holmberg (2010) recorded group conversations among music teachers in Swedish schools of music and arts, and analysed them discursively. She found changed conditions in the teachers’ work, and discussed those findings in relation to tendencies in late modernity. The relevance of Holmberg’s study relates to the Swedish and Norwegian schools having much in common, and to its discussion of power relations within the field. She does not, however, address teachers’ professional identities directly. Of Nordic studies on teacher identity, Søreide’s (2007) thesis is relevant. She investigated how teacher identity is narratively constructed within the Norwegian elementary school system, drawing on interviews with female teachers, public school policy documents, and written material from Norway’s largest professional association for teachers, the Union of Education Norway2 (Søreide, 2007). Public narratives about teachers were the unit of analysis, where the identity construction of “the teacher as pupil centred, caring and including” was identified as especially paramount (Søreide, 2007). She combines poststructuralist, discursive and narrative approaches to identity, where subject positions are central in the analysis. Her thesis forms a methodological backdrop to my research, although my research field and combination of discourse theory and theories of professions differ from her field of research and theoretical perspectives.

Most of the discourse-oriented studies within the Nordic music educational field build on Foucault. Krüger’s (1998) research on teacher practice, pedagogical discourse and construction of knowledge was one of the first of these studies. Krüger (1998) followed the everyday life of two music teachers in a Norwegian compulsory school for six months, interviewed them, and investigated how they constructed their practice. He identified how the teachers’ practices and norms were inscribed in discourses and relationships of power and knowledge. Nerland (2003) also built on Foucault, in her study on teaching practices in higher music education in Norway, where teaching was seen as cultural practices that are historically and socially constituted. Other research building on Foucault is Ellefsen’s (2014) in-depth study of a Norwegian upper secondary educational programme in music called “Musikklinja”. The study was ethnographic, with observations of, and interviews with, students, and it aimed at understanding how student subjectivities were constituted in and through discursive practices of musicianship (Ellefsen, 2014). Ellefsen and Karlsen (2019) have performed a Foucauldian discourse analysis of the curriculum framework for the Norwegian municipal school of music and performing arts, investigating the meanings of “diversity”. They identified four nodal points showing different ways of understanding diversity, namely: diversity understood as difference in students’ ethno-cultural backgrounds, diversity of educational opportunities and modes of expression, diversity and/or/as deeper understanding, and diversity of learning arenas and contexts. These studies have laid the ground for seeing the music educational field discursively, and so have opened up for addressing power relations and struggles over definitions. My research contributes by using another approach to discourse analysis and another unit of analysis, namely professional identity.

Relevant research on professionalism and education includes Mausethagen’s (2013) study on how the teaching profession constructs and negotiates professionalism in Norwegian national policy. Her findings suggest that the teaching profession in Norway has become more proactive in creating legitimacy for their work, and that both the teacher union and individual teachers try to resist external control, such as national testing (Mausethagen, 2013). Georgii-Hemming (2013) asserts in the concluding chapter of the anthology Professional knowledge in music teacher education (Georgii-Hemming, Burnard & Holgersen, 2013) that music teacher education has an important mission in educating professional music teachers, and that well-founded pedagogical knowledge, reflections on values, and interpretation precedence are important for working towards that mission. She also argues that a “carefully considered music-pedagogical philosophy” is crucial in order to develop professional knowledge not only for the individual teachers, but also for the music teacher profession as a whole (Georgii-Hemming, 2013, p. 210). Research on professionalism and education forms a backdrop for my understanding of music teaching as part of a professional field, which I built on and combined with a discursive approach and focus on identity.

Discourse theory and analysis

There are several approaches to discourse analysis, and some focus on the content of language in use while others on its structure (grammar) (Gee, 2014). Laclau and Mouffe’s (2001) discourse theory represents the former group, focusing on both language and practices in order to analyse power relationships and identity construction. Laclau (1990, p. 100) emphasises that discourse is not a combination of speech and writing, “but rather that speech and writing are themselves but internal components of discursive totalities”, and that the “totality which includes within itself the linguistic and the non-linguistic, is what we call discourse”. Laclau and Mouffe (2001) understand everything as discursively constructed, meaning that social practices are fully discursive. This does not imply that they deny the existence of physical objects. Rather, they believe that our access to them is through discourses because we ascribe meaning to physical objects through discourses (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). For example, anyone who sees a drum can declare that the thing they see exists, but perceiving it as a musical instrument, and not just a round object with skins, is discursively constructed. If one was outside any musical discourse, one might perceive of the “round object with skins” as, for example, a table. What is not part of a particular discourse belongs to the field of discursivity, which is “the necessary terrain for the constitution of every social practice” (Laclau & Mouffe 2001, p. 98). In this article, I speak of the “school of music and arts field” as a terrain for the constitution of social practices within, or related to, the school of music and arts.

Struggles over meaning are central in discourse theory, where meaning can never be completely fixed (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). Accordingly, there will always be disagreements about definitions of identity and the social as we strive to fix the meaning of signs by placing them in relation to other signs (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002). In order to identify these processes, Laclau and Mouffe (2001) provide a theoretical framework. In this framework, moments are signs that have their meaning (partially) fixed through articulation in a discourse, whereas elements are signs with several competing ways of understanding them, as their meaning has not yet been fixed (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). The fixation of meaning in comparison to what-it-is-not is central in discourse theory. Laclau and Mouffe (2001, p. 92) emphasise that “all values are values of opposition and are defined only by their difference”. A complete fixation of signs is never possible, though, because every fixation of a sign is contingent.

Nodal points are privileged signs that play a central role in (partially) fixing the meaning (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). Nodal points are empty; there are several ways of interpreting them, which make them an arena for discursive struggle. They acquire their meaning by being related to other signs in chains of equivalence, where a discourse is formed by the fixation of meaning around a nodal point (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). Floating signifiers are also empty and open; they are “incapable of being wholly articulated to a discursive chain” (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001, p. 99). They refer to the struggle between discourses to fix meaning of signs and create (temporarily) hegemony. An example of this is the different ways of seeing and articulating migrants. “Migrant” could be a floating signifier where various discourses try to define it: as refugees in need of protection, as social resources to our multicultural society, as a valuable workforce in the labour market, or as a potential threat to our security or cultural heritage. A discourse is a fixation of elements to moments within a specific domain, while hegemony refers to fixation across discourses. When one discourse dominates alone, a hegemonic intervention has been a success (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001).

If the world is perceived as discursively constructed, it follows that identities are discursive. Identity is understood as temporary attachment to subject positions where the subject is multiply constructed across different discourses and practices (Hall, 1996). To identify with something means there must be something with which you do not identify. Identity is thus constructed through difference, to what it is not (Hall, 1996; Laclau, 1990). Through chains of equivalence, signifiers are linked together around a nodal point of identity, which different discourses try to fill with content (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). In my analysis, ‘school of music and arts music teacher’ (‘musikklærer i kulturskolen’) was the nodal point for music teachers’ professional identities, because it was not clear what it meant to be a music teacher in the school of music and arts; there were different ways of interpreting “music teacher” within the field. Different discourses tried to fill the nodal point with content, and they offered subject positions for music teachers to identify with. This nodal point was installed as part of the discursive “skeleton” which guided the analysis. Hence, it derived from theory/methodology, but in combination with background knowledge and findings from the data.

Within a discursive approach, identities are seen as contingent since they could have been, and can become, different (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). They are also seen as relational, since no identity can be fully constituted (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). The subject thus has some degree of agency to identify, or not, with particular subject positions. The subject is also overdetermined, which means it is positioned by several conflicting discourses (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). Overdetermination implies a rising of conflicts between subject positions, and a terrain for hegemonic articulation (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). It also means that the subject might identify variously according to the situation. A teacher could identify with the subject position Music Teacher when s/he teaches music groups in compulsory schools and with Instrumental Teacher when s/he gives trumpet lessons. Although the subject is constructed within discourses, different discourse analytical approaches open up for more or less agency: the subject’s degree of freedom of action (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002). Within Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse theory, the subject is, to a large degree, perceived to be determined by structures. I, however, perceive the subject as having some degree of agency, with the possibility to resist ideological domination, but with discourses limiting the subjects’ freedom of action.

Discourse of professionalism and professional identity

My aim was to investigate music teachers’ professional identity, which means the focus was on identities connected to their profession. Understanding music teaching as a profession, something for which I have argued in a previous article (Jordhus-Lier, 2015), was thus a prerequisite for discussing the findings in relation to theories of professions (Abbott, 1988; Freidson, 2001; Molander & Terum, 2008). This provided me with an entrance to a better understanding of the connections between the teachers and logics operating in their professional environment. These logics enable the teachers’ possibilities for action, and can be understood as systems or ideologies – or professions or discourses. However, including theories of professions in a discourse-oriented study implies combining discursive and non-discursive theories. Laclau and Mouffe (2001) understand everything as discursively constructed, as opposed to most theories of professions. Common to both, however, is that they provide systems for understanding the social: discourse theory through discourses, and theories of professions through logics or ideologies.

In building my theoretical and analytical framework, I chose to integrate theories of professions in the concept of professionalism: understood discursively as a discourse of professionalism. A discourse could be understood as a system having a certain degree of regularity, which “constructs the reality for its subjects” (Dunn & Neumann, 2016, p. 4). Seeing professionalism as a discourse thus requires understanding the system as socially constructed, as a system constructed through language that has influence because someone has spoken on its behalf. It is a system that is constitutive for occupations, work places and professional identities. In the literature on professions, “professionalism”, “professionalisation” and “professions” are understood as, among other things, systems, logics, values, or ideologies – all of which have some kind of regularity. Abbott (1988) understands professions as a system and Freidson (2001) interprets professionalism as a logic. Evetts (2006) claims there has been a shift of emphasis in the sociology of professions, first from professionalism to profession understood as a generic category of occupational work, then via processes of professionalisation towards a return to professionalism – interpreted as a discourse of occupational change and managerial control.

My understanding of professionalism as a discourse is informed by theories of professions, in particular Freidson’s (2001) interpretation of professionalism as the third logic of organising work, opposed both to the logics of the market, where work is controlled by consumers, and to the firm (bureaucracy), where managers are in control. The third logic is a description of an “ideal-type” profession and not of “reality” (Freidson, 2001), and I therefore assert that it could be understood as socially constructed. When building my theoretical framework, I understood ‘organising of work’ as a nodal point and floating signifier that the discourse of professionalism and other discourses tried to fill with meaning. These other discourses were, for instance, those Freidson (2001) describes as logics: those of the free market and bureaucracy. I found the nodal point ‘organising of work’ getting its meaning within the discourse of professionalism by being related to signifiers like ‘monopoly’, ‘freedom of judgement’, ‘discretion’ and ‘autonomy’ (Abbott, 1988; Freidson, 2001; Molander & Terum, 2008). Following from that, ‘organising of work’ is related to other signifiers in other discourses, for instance ‘competition’ in the discourse (or logic) of the free market, and ‘efficiency’ in the discourse (or logic) of bureaucracy. There is support for a discursive understanding of professionalism in the literature (Evetts, 2006; Evans, 2008). Evetts (2006) sees professionalism as a discourse of occupational change and social control, distinguishing between the discourse of organisational professionalism constructed from above (managers) and the discourse of occupational professionalism constructed from within. The latter is based on autonomy and discretionary judgement by practitioners in complex cases and depends on education, vocational training and development of strong occupational identities and work cultures (Evetts, 2006). This resembles the discourse of professionalism that my research builds on.

Professional identity involves both individual and collective identity. Heggen (2008) emphasises that, in professions, collective identity is constructed as members endorse a unified symbol and share a common understanding, whereas the members’ individual professional identities concern self-identity in combination with the practice of a professional role. The collective identity could then be unified at the same time as individual identities are diverse (Heggen, 2008). Group formation is a reduction of possibilities, where some possibilities of identification are put forward and others are ignored (Jørgensen & Phillips, 2002). This relates to the idea that collective identity only exists when constructed as difference, which implies a we/they distinction (Mouffe, 2005). Professional identities of music teachers is thus about how they see themselves in the field, both individually and as part of groups (professions). This is something discourse analysis could reveal, because central to the development of professional identities is identification with subject positions (as identity is understood as temporary attachment to subject positions) and positioning vis-à-vis other groups. Both are connected and related to central discourses in the field.

Research design, validity and ethics

The data material for my research on professional identities of music teachers consisted of qualitative semi-structured interviews with sixteen music teachers from three different schools of music and arts, and document analysis of curriculum frameworks (Norsk kulturskoleråd, 2003, 2016) and policy documents (Conservative Party, 2015; Ministry of Culture, 2009; Ministry of Education and Research, 2014; Office of the Prime Minister, 2013). When performing a discourse analysis on this data material, the interviews provided me with information about how teachers construct meanings about their professional identities and the schools, and the documents demonstrated how policy makers and politicians construct meanings within the school of music and arts. The data was collected and analysed to answer the following research questions: i) Which discourses compete in the Norwegian municipal schools of music and performing arts? and ii) How are music teachers’ professional identities constructed within these discourses?

Brinkmann and Kvale (2015) emphasise the craftsmanship of the researcher, especially in research building on theories that dismiss an objective reality against which findings could be measured. A researcher’s special qualifications to interpret data could thus help in justifying discourse analytical research and increasing validity (Taylor, 2001a). In-depth knowledge of the study field requires careful handling, however, encouraging the researcher to be critically reflexive in her/his role as researcher. This is crucial to a study’s validity, and includes clarifying similarities and differences between oneself and the participants, and accounting for one’s own position in, and experience with, the field of study (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2009). The identity of the researcher is relevant as it can influence both the selection of topic, the data collection, and the interpretation and analysis (Taylor, 2001b). My choice of topic derived from my own experience as music teacher, an experience that also affected my interpretation and analysis as I often knew more about a topic than could be read from the data. I tried, however, to use this knowledge to contextualise and “see the bigger picture”. This relates to Neumann’s (2001) assertion that a researcher’s general and cultural knowledge of the area of study is a central prerequisite which must be fulfilled before research can begin. However, focusing on similarities with participants could lead to differences being toned down and to the false belief that there are no power differences between the researcher and the participants (Taylor, 2001a). While I shared their experience as music teachers, I also performed the role of a researcher. I was “one of them” in the sense that I could understand and contextualise what the informants told me, but I was still not a colleague, and was going to use the information they gave. Although my experience was that the informants spoke openly, there may well have been things they did not tell me or issues they did not explain fully.

In order to maintain the anonymity of the participants, I gave fictitious names to teachers as well as to their schools. In addition, I deliberately tried to “blur” the teachers’ narratives so they cannot so easily be traced. This was done by focusing more on discourses, subject positions, struggles and hierarchy rather than following the different teachers’ stories and narratives. This way, I focused on structures in the field and how the various teachers manoeuvred within them. The school of music and arts field was at the centre of the analysis, not the individual teachers. Doing a discourse analysis, and not a narrative analysis, for example, was helpful in this regard. However, it also had its challenges. On the one hand, it required me to give thick descriptions and show how the data material had been used, and on the other, this had to be balanced against maintaining the informants’ anonymity. I also did a member check, sending transcripts back to the informants for approval and comments. Member check as a form of validity is, however, problematic in discourse analytical studies, because the transcript would be an interpretation and an analysis based on theory, and therefore could be difficult for non-academics to validate (Taylor, 2001a). I therefore limited this exercise to sharing the material used in the analysis with the informants, and simply sought active confirmation that they still wanted to participate. This exchange, or interplay, however, raises ethical questions rather than questions about validity (Riessman, 2008).

Teachers and schools of music and arts were selected purposefully in order to acquire rich information about the field and the teachers’ professional identities. I selected schools and teachers i) according to a given set of criteria, and ii) according to the purposeful sampling strategy maximum variation sampling (Patton, 2015). The criteria for school selection ensured inclusion of schools with institutional collaboration and offering a wide range of arts options, and ensured that they were of an appropriate size. I selected middle-sized schools in order to have a sufficient number of teachers to select from while being able to maintain the informants’ anonymity. Maximum variation sampling was then used in further selection of the schools, based on a variety of institutional collaboration and geographical dispersion. In selecting teachers, I set the following criteria: all should have a degree in music education or music performance, be employed as a music teacher in the school of music and arts, and have at least a 40% employment position (in order to be able to give rich information). Maximum variation sampling (Patton, 2015) was used in the further selections, based on: instrument, age, seniority, genre, gender, pedagogical education, and collaboration with compulsory schools, upper secondary schools, and/or local community music and arts fields. Both men and women were represented, and their ages ranged from around twenty-five to nearly sixty. Three had background from popular music, while the rest were classically trained. Some also played and taught folk music or contemporary music. The informant selection included teachers of string instruments, piano, woodwind instruments, brass instruments and guitar, as well as vocal teachers. The interview guide consisted of four topics: background, understanding of professional identity, the school of music and arts as local resource centre, and the future of the teachers and the school.

Analysis and interpretation

The analytical process was circular: going back and forth between coding the material and analysing it, drawing preliminary conclusions which could lead to adding something to the matrix to test the conclusion. This can be described as an iterative process (Miles, Huberman & Saldaña, 2014; Taylor, 2001b). Some codes derived from theory, previous research and my background knowledge. Examples of such codes are ‘tacit knowledge’, ‘expertise’ and ‘collective identity’. Most of the codes, however, emerged from the material in an open coding process (Tjora, 2017). The code ‘colleagues are the reason I work in a school of music and arts’ is an example of a code that emerged from the data. Open coding is time-consuming and one could end up with a huge number of codes, but it contributes in the process of understanding what the data material says (Tjora, 2017). When the number of codes increased, however, I started merging and organising them into categories and hierarchies. An example of this is the organising of the codes ‘being challenged’, ‘collaborate in teaching’, ‘different competences is good for collaboration’ and ‘easier when meeting often’ under the category ‘collaborate with other teachers’. This category was then, together with other categories such as ‘change in degree of collaboration’, ‘collaborate with teachers from other arts fields’ and ‘collaboration higher education’ organised into the category ‘collaboration’.

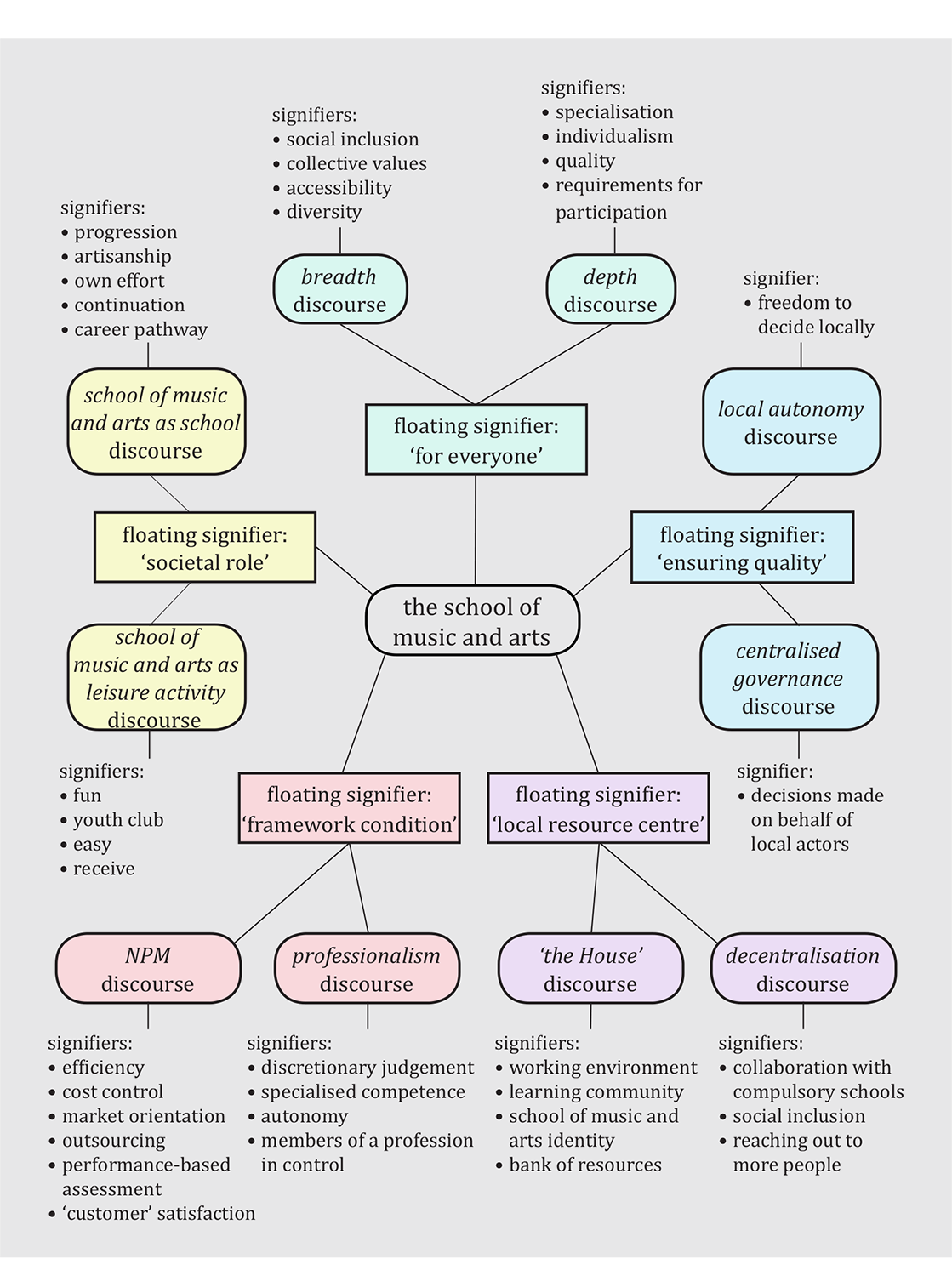

The concepts of elements, nodal points, floating signifiers, chains of equivalence, discourses and subject positions were central during the analytical process. Identifying competing discourses in the school of music and arts field was the point of entry. I searched for elements, which are open signs where their meaning has not yet been fixed (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). Hence, I searched to find concepts which could be understood in various ways. This allowed me to focus on struggles over central issues in the field, as well as how they were contested and negotiated. In such processes, I was able to single out issues that were somehow hidden at first glance. After having singled out several elements in the documents, I aimed at identifying discourses that tried to fill these elements with meaning. ‘School of music and arts for everyone’ and ‘quality’ are examples of elements I singled out, because it was not clear how these concepts were understood in the documents. This relates, among other things, to whether the school should be easily accessible or organised for those who want to put in extra effort. ‘Quality’ was one of the terms that occurred frequently in the documents, but it was not clear what was meant. One understanding took quality as being opposed to breadth. In the further analysis, ‘for everyone’ became a floating signifier and ‘quality’ a signifier articulating the depth discourse (see Figure 1).

After having identified elements and discourses in the material, nodal points (privileged signs that play a central role in the fixation of meaning) were next in line. The most central elements from the analysis were identified as nodal points. Nodal points are empty; they get their meaning by being related to other signs (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). Therefore, the further analytical process involved identifying other signs in relation to the nodal points. A discourse is formed by the (partial) fixation of meaning around a nodal point (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001), and the following analytical process led to “re-identifying” discourses by taking new findings back to the discourses identified earlier in the process. I found that there were several opposing discourses in the field, and most of the nodal points were therefore also identified as floating signifiers, which refers to struggle between discourses (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). These floating signifiers became the “skeleton” of the findings (see Figure 1 and 2). The analytical process identified various signifiers in different chains of equivalence articulating the same floating signifier, which led to the identification of competing discourses. ‘For everyone’, which was first identified as (part of) an element, became in the further analysis a nodal point because of its centrality in the meaning-making: it is significant when identifying what kind of institution the school of music and arts is or should be, and it is central because the curriculum framework (Norsk kulturskoleråd, 2016) states that the school should be for everyone who wants to enroll. When identifying other signs in relation to this nodal point, like for instance ‘social inclusion’ and ‘collective values’, but also ‘individualism’ and ‘specialisation’, I found two opposing discourses trying to fill it with content. ‘For everyone’ therefore became a floating signifier with the two binary discourses of breadth and of depth trying to articulate it (see Figure 1).

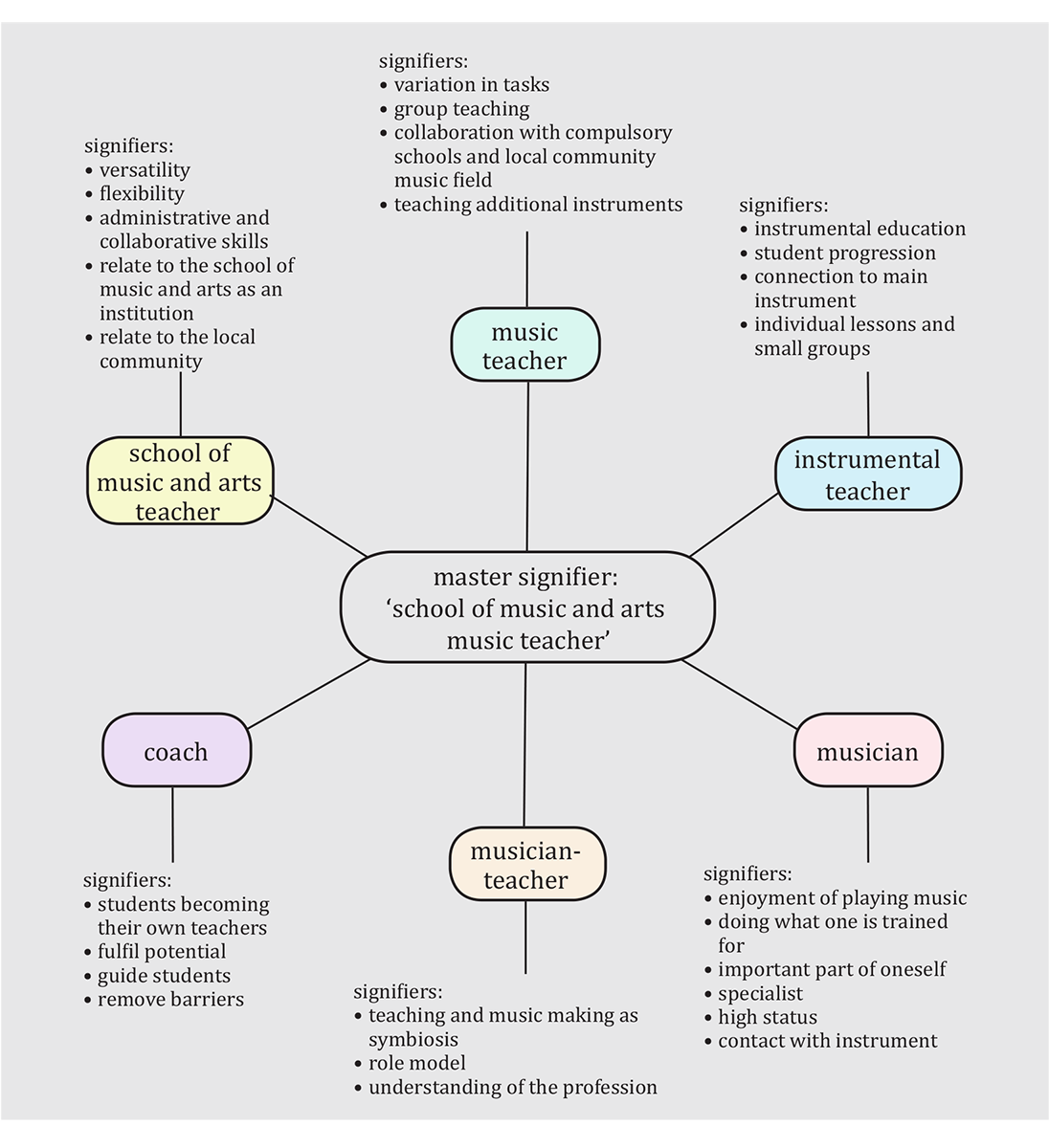

The first step in searching for subject positions available to teachers was to identify the master signifier/nodal point of identity. What unified informants was their position as music teachers in schools of music and arts. Hence, ‘school of music and arts music teacher’ (‘musikklærer i kulturskolen’) became the nodal point of music teachers’ professional identities. The process of identifying subject positions involved investigating how this nodal point was articulated by discourses into subject positions by being linked to signifiers in chains of equivalence. One example of this is how Music Teacher emerged through the analytical process as a subject position where the signifiers ‘variation in tasks’, ‘group teaching’, ‘collaboration with compulsory schools and the local community music field’, and ‘teaching additional instruments’ were linked to the nodal point. These signifiers also pointed to the subject position Music Teacher being articulated by the institutional discourses of breadth and decentralisation and the teacher discourses of versatility and collaboration. Here is an example of how the subject position Music Teacher was constructed within the breadth and versatility discourses, because of the emphasis on variation in tasks. One of the teachers I interviewed said:

I feel I am doing a lot of different things, which fits with being a music teacher, […] it embraces a lot, I think. […] Conductor, musician, I feel everything is embraced by music teacher. (Nora)

The process of identifying subject positions went on simultaneously with the previously described analytical process of identifying competing discourses in the field. Discourse theory and theories of professions underpinned the analysis throughout the process, and I used central theoretical concepts to discuss the findings. Theories of professions were, for example, most central in the articulation of the floating signifier ‘framework condition’, with the New Public Management discourse and the professionalism discourse both contesting its definition.

Results of the research

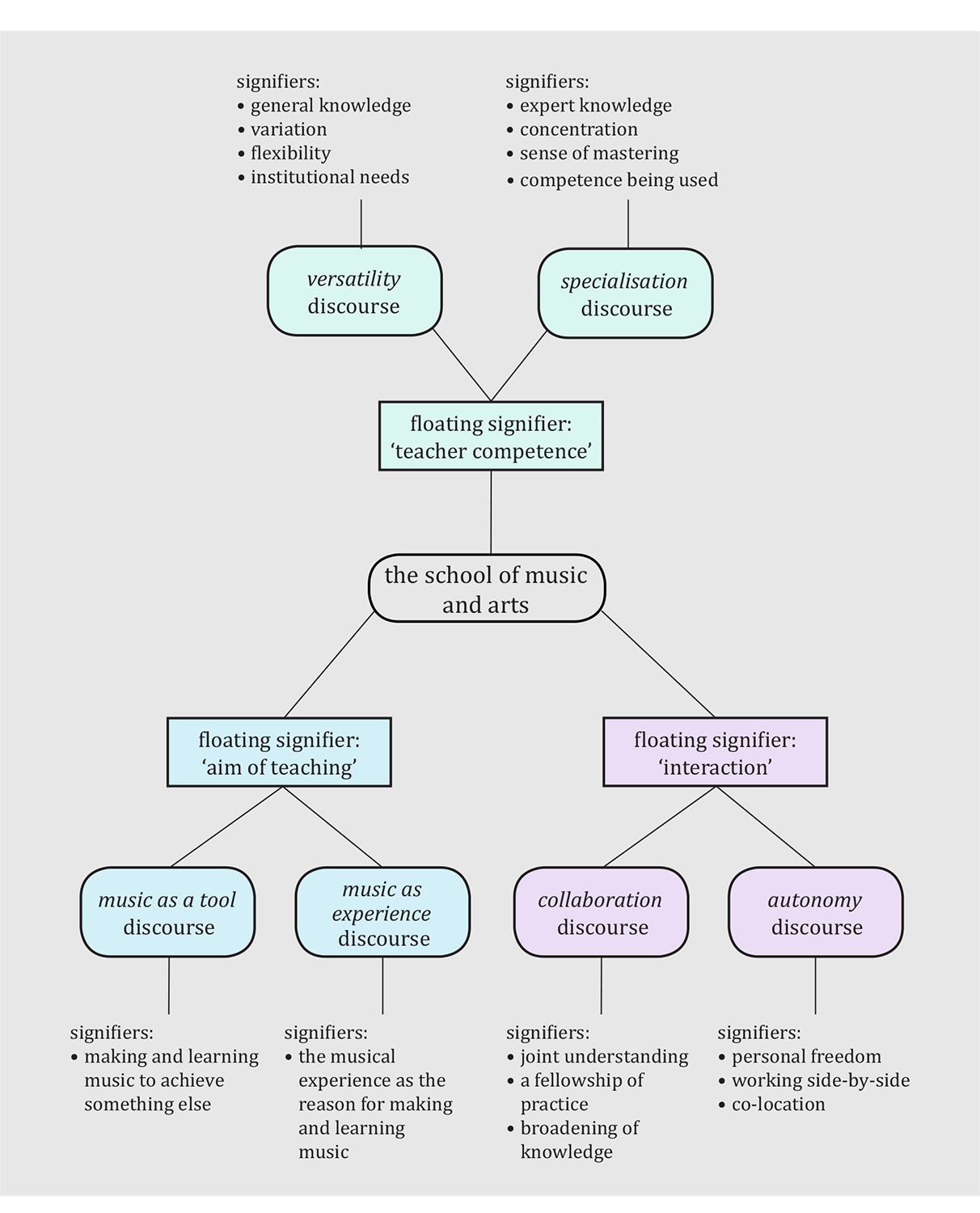

By carrying out a discourse analysis based on Laclau and Mouffe’s (2001) discourse theory, I revealed several binary institutional and teacher discourses within the field, as well as six distinct subject positions constructed within these discourses. The institutional discourses were trying to imbue ‘institution’ with meaning; hence ‘institution’ appeared as nodal point and floating signifier. The analysis did not identify any one single discourse as hegemonic; rather, there were several discourses at play in the field. These were the binary discourses of breadth and depth, of local autonomy and centralised governance, of ‘the House’ and decentralisation, of New Public Management and professionalism, and of school of music and arts as school and school of music and arts as leisure activity (see Figure 1). The teacher discourses concerned and articulated perceptions of what a teacher in the school of music and arts is; they tried to imbue ‘teacher’ with meaning, which made ‘teacher’ the nodal point and floating signifier. ‘Institution’ and ‘teacher’ were installed as nodal points as part of the theoretical and analytical framework guiding the analysis, but also because I found in the data that there were different ways of understanding those concepts. The teacher discourses were the binary discourses of versatility and specialisation, of collaboration and autonomy, and of music as a tool and music as experience (see Figure 2). These binary oppositions should be understood as struggles to fill distinct floating signifiers with meaning, and they were established by a set of signifiers linked in chains of equivalence. These floating signifiers emerged from the data. One example is the role of the school in society. In the data, there were several ways of understanding the role of the school, which made ‘societal role’ a floating signifier. The most prominent ways to understand it were i) the school of music and arts as a school focusing on students’ progression, putting in effort, career pathway and continuation, and ii) the school as leisure activity with emphasise on having fun, being easy and receiving (as opposed to putting in effort). This way of doing the analysis contributed to revealing tensions in the field.

Six subject positions were identified through interview statements about teaching and the teacher role, and through the representations of ‘school of music and arts music teacher’ (‘musikklærer i kulturskolen’) in the document material. This means these subject positions were constructed within the discourses in the field, through language used by teachers and in the documents. The subject positions were Music Teacher, Instrumental Teacher, Musician, Musician-Teacher, Coach and School of Music and Arts Teacher (Kulturskolelærer). Most of the teachers identified with several subject positions, either at the same time or interchangeably, according to the situation (see also Jordhus-Lier, 2021). Subject positions constructed within opposing discourses, however, are difficult for teachers to identify with, especially at the same time. The aim of addressing these subject positions was to answer the second research question, namely how music teachers’ professional identities are constructed within the discourses in the school of music and arts. This relates to the logic of subjects acquiring their identities through identification with subject positions (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). The discursive relations between the six identified subject positions and the nodal point of identity is visualised in Figure 3 below, which also shows how each of these subject positions was established by a set of signifiers linked in chains of equivalence.

Discussion

Based on the findings of central discourses and available subject positions, I was able to address power relations, status hierarchies, and tensions within the school of music and arts. As for the field in general, tensions between the institutional discourses of breadth and depth and between the teacher discourses of versatility and specialisation were most prominent. The discourses in these two sets of binaries articulated the same signifiers (breadth/depth ‘for everyone’ and versatility/specialisation ‘teacher competence’) in order to achieve hegemony. Revealing this tension between different ways of understanding the institution and the teachers led to the insight that it was difficult for the teachers to identify with subject positions constructed within binary discourses at the same time. As a consequence, their professional identities needed to be negotiated. The possible conflict between subject positions constructed within discourses in binary opposition could also lead to different views on the aim of teaching, who the school should be for, and what to prioritise. This relates to the relationship between structure and agency, where the school of music and arts field is understood as the structure and the music teachers as agents. By carrying out a discourse analysis, I was able to reveal how the field is structured by discourses, and further how subject positions are constructed within them. This led to an insight into how music teachers working in this field are conditioned by these structures, but granted agency to i) identify with various available subject positions, and ii) resist structural constraints (dominating discourses and available subject positions) to try to change the field. This is evident in how one of the teachers, Laura, explained the resistance to the system regulating quality.

The progression of a student is not statutory, which means it is quite open. […] I guess it is about what I, as a professional practitioner, think it should be. But if others tell me I am wrong, I have to accept that. But at the same time, I almost feel schizophrenic about this. Because I see that I have to function within the system, but at the same time, there is something inside telling me that I really feel something else. (Laura)

Visible in this statement is a conflict between the system’s and Laura’s view of ensuring quality through student progression. We do not know how she will handle this conflict, but she could identify with a subject position constructed within the school of music and arts as leisure activity discourse, where progression is not seen as important, or she could resist, and try to establish the school discourse as dominant in the school of music and arts field. It would probably also be possible to reveal conflicts without using discourse analysis, but in order to understand where these conflicts are grounded, what they could lead to, as well as possible ways of handling them, a discursive approach was helpful.

In discourse theory, the fixation of meaning in comparison to what-it-is-not is central – that is, where something is defined through its difference to something else (Laclau & Mouffe, 2001). This is also the case for identity. Mouffe (2005) claims that creation of an identity implies the formation of difference, and that difference is often constructed on the foundation of a hierarchy. Building on discourse theory when studying identity could thus lead to identifying hierarchies. My analysis revealed the subject positions to be hierarchically structured, where positions constructed within the discourses of depth and specialisation had a somewhat higher status than those constructed within the versatility and breadth discourses. This is evident in how one of the teachers talked about not seeing himself as a musician.

It [to be a musician] has higher status in music communities, […] and to be a top musician, then people start looking up to you. I feel I am not there, that I am not part of the gang. I would love to be counted in when someone is looking for freelance musicians or someone to hold a seminar. (Kristoffer)

Kristoffer identified with the subject positions Music Teacher and Instrumental Teacher, but not with the subject position Musician.

The discursive structure also made it possible to discover tensions between different actors, because the analytical structure of floating signifiers and discourses makes it easier to reveal who understands what in which ways. An example of this is how I, through the analysis, found the institutional discourse of breadth to be dominant in policy documents, while the teacher discourse of specialisation was dominant in the interview material. This is further visible in available subject positions and how professions are constructed and understood. The music teachers identified with several subject positions, but in the curriculum frameworks, School of Music and Arts Teacher was the primary subject position. This means that, within the documents, there were signs of a desire to unite teachers around common features, while the interview material, to a greater extent, supported an understanding of the school as a plurality of specialists and specialisations. This connects to collective professional identity: membership in professions. Some teachers linked their profession to their instrument, others saw music teaching as their profession, but none of them perceived of the broader school of music and arts teaching as their profession. However, School of Music and Arts Teacher is the dominating subject position in the curriculum framework, which could point towards the curriculum framework indicating school of music and arts teaching as the profession in which all teachers are members. Here, the institution is central in the profession and could provide the school and its teachers with a stronger political voice. On the other hand, perceiving music teaching as the profession means that members share a common subject, music. This would exclude teachers from other art forms than music, but could include music teachers who work outside the school.

My research also highlighted some possible pitfalls when using discourse analysis. The first pitfall regards the discursive understanding of non-discursive theories. Theories of professions contributed in explaining structures and processes connected to professions and the labour market, which is relevant and fruitful in itself. Understanding these theories as a discourse of professionalism implicated an extra layer in the theoretical framework, which complicates the analytical presentation. I also experienced the process of combining discursive and non-discursive theories challenging, and believe the greatest challenge is making the theoretical framework sufficiently explicit in order to communicate the analysis and its findings. The second pitfall regards distinguishing between the concepts of subject positions and identity. Unless subject positions as theoretical constructs are sufficiently explained, readers might easily believe that a particular informant is a music teacher, while another is an instrumental teacher. This misinterpretation would lend legitimacy to the assumption that the discourse analysis portrays a variety of teachers within the school, instead of identifying available subject positions, which each teacher can identify with (or reject). It is in enabling this latter task, showing how teachers negotiate their identities, that discourse analysis displays its merits. To be able to discover those issues, the structure of subject positions has to be clear all the way from setting up the theoretical framework to performing the analysis and interpretation. Clarity, structure and thick descriptions are crucial in order to avoid these pitfalls.

The analytical approach put forward conceives of discursive fields as built on binary oppositions. This is due to the importance of difference in constructing meaning and in identification within the theoretical framework of this research (Mouffe, 2005; Laclau & Mouffe, 2001), and the analytical model which focused on identification of floating signifiers which different discourses tried to imbue with meaning. This way of organising the analysis and findings is open to debate, of course, and it raises questions like: Why binaries? Why cannot a third discourse attempt to imbue a floating signifier with meaning? Indeed, a third discourse could most likely attempt to imbue meaning to a floating signifier in an analysis that was differently structured. But the discursive structure did highlight not only the discourses in binary oppositions, but also their struggle over defining the institution and the teachers. And, within all those discourses, the various subject positions with which the teachers could identify were constructed, contested and negotiated.

Concluding remarks

The discursive approach of my research represents a theoretical and a methodological contribution to research within the field of music education, demonstrating how discourse analysis provides analytical tools that can open the research field and challenge taken-for-granted knowledge, discover binary discursive oppositions, and unmask power relations. Before I elaborate on the contributions, I will point to some things this discourse analysis did not provide. It did not focus on the stories of the teachers in ways a narrative analysis would have done. Rather than honing in on each teacher’s professional life story, this analysis focused on the discursive field, looking for meanings across teacher narratives. A combination of narrative and discourse analysis could have opened analytical possibilities, but also complicated the research further. One could also ask what thematic analysis would add to such a study? Identifying relevant themes across the teachers’ stories would be beneficial, particularly if a comparison between different professional fields was a stated research objective. A thematic analysis structured by theory would arguably also have the potential of producing a clearer and less “messy” analysis. However, such a thematic analysis would come at the expense of discovering structures within the field and investigating how different teachers navigate them. In discourse analysis, the focus on meanings constructed in the field and the structure of the findings deriving both from theory and empirical data often make the analysis somewhat tangled. One of the methodological contributions of my research is thus its explicit embrace of complexity and “messiness”. This is also evident in the construction of professional identities, where various discourses and subject positions are in a continuous struggle to fix meaning over central elements. This “messiness”, I would argue, contributes to broadening a field of research that hitherto has conceived of music teacher identities as primarily centred on the teacher–musician dichotomy. My analysis also invites critical scrutiny of other dichotomies, such as that between versatility and specialisation.

Using discourse analysis to understand professional music teacher identity could not only benefit the research field, but also policy makers, the practice field and teachers in their further development of practice and negotiation of identities. The findings of my research can lead to a raised awareness about individualism versus collective values, the school as a school versus leisure activity, and music as a tool versus experience – all of which can contribute to an increase in teachers’ reflections around, and development of, their practice. Both specialised and versatile teacher competences are important in the school, but teachers struggle to maintain both. My research points to other solutions than that of all teachers successfully straddling both ideals, namely i) encouraging a broad understanding of specialisation, for instance specialists in “group teaching” or “general music”, and ii) emphasising both teacher and institutional collaboration (see also Jordhus-Lier, 2018). This is again relevant for higher music education institutions in their efforts to educate music teachers who are specialists, while also being flexible and equipped with knowledge about the school of music and arts. I suggest there is a need to educate “open-minded specialists” through broad-based teacher education that includes possibilities for specialisation and lays the groundwork for flexible music teachers who are able to develop their competence after graduation. Offering an education that is too broad could lead to all teachers becoming versatile while not allowing any to develop as specialists. This could make the school of music and arts less versatile, because the teachers would all have roughly the same competence. The methodological contributions for higher music education could, however, just as much be related to function as an inspiration not only for music education researchers, but also for music teacher educators in their discussion of professional identities with students. In this respect, my analytical framework offers a lens through which to look at teachers, or oneself, within the practice field. In doing so, the objective should not be to identify the same discourses and subject positions in other settings, but for teachers, students and researchers to use the structure of nodal points, floating signifiers, signifiers, subject positions and discourses to discover new struggles and new knowledge – which can build on the findings of my research and further develop the music education research field and the field of practice.

References

- Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. University of Chicago Press.

- Alvesson, M. & Sköldberg, K. (2009). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Angelo, E. (2012). Profesjonsforståelser i instrumentalpedagogiske praksiser [Philosophies of work in instrumental music education] [Doctoral dissertation, NTNU]. NTNU Open. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/270300

- Angelo, E. & Kalsnes, S. (Eds.). (2014). Kunstner eller lærer? Profesjonsdilemmaer i musikk- og kunstpedagogisk utdanning [Artist or teacher? Professional dilemmas in the music- and arts educational field]. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Berge, O. K., Angelo, E., Heian, M. T. & Emstad, A. B. (2019). Kultur + skole = sant. Kunnskapsgrunnlag om den kommunale kulturskolen i Norge [Knowledge base for the municipal school of music and performing arts in Norway]. Telemarksforskning. https://intra.tmforsk.no/publikasjoner/filer/3487.pdf

- Bernard, R. (2005). Making music, making selves: A call for reframing music teacher education. Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education, 4(2).

- Bouij, C. (1998). “Musik – mitt liv och kommande levebröd”. En studie i musiklärares yrkessocialisation [“Music – my life and forthcoming livelihood”. A study in music teachers’ vocational socialisation] [Doctoral dissertation, Göteborg universitet]. GUPEA. http://hdl.handle.net/2077/16399

- Brinkmann, S. & Kvale, S. (2015). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Broman-Kananen, U.-B. (2009). Ett eget tidsrum: Musikpedagogernas identitetsprojekt i de finländska musiklärorinrättningarna [Music teachers’ identity project in Finnish music institutions]. Musiikki, 39(1).

- Conservative Party. (2015). Kulturskole [School of music and performing arts]. Retrieved 23.05, 2015, from https://hoyre.no/politikk/temaer/kultur/kulturskole/

- Dunn, K. C. & Neumann, I. B. (2016). Undertaking discourse analysis for social research. University of Michigan Press.

- Ellefsen, L. W. (2014). Negotiating musicianship. The constitution of student subjectivities in and through discursive practices of musicianship in “Musikklinja” [Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian Academy of Music]. Brage. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/227601

- Ellefsen, L. W. & Karlsen, S. (2019). Discourses of diversity in music education: The curriculum framework of the Norwegian schools of music and performing arts as a case. Research studies in music education, 0(0), 1321103X19843205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103x19843205

- Evans, L. (2008). Professionalism, professionality and the development of education professionals. British Journal of Educational Studies, 56(1), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2007.00392.x

- Evetts, J. (2006). Introduction: Trust and professionalism: Challenges and occupational changes. Current Sociology, 54(4), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392106065083

- Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism. The third logic. Polity Press.

- Gee, J. P. (2014). An Introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. Routledge.

- Georgii-Hemming, E. (2013). Meeting the challenges of music teacher education. In E. Georgii-Hemming, P. Burnard & S.-E. Holgersen (Eds.), Professional knowledge in music teacher education (pp. 203–213). Ashgate.

- Georgii-Hemming, E., Burnard, P. & Holgersen, S.-E. (Eds.). (2013). Professional knowledge in music teacher education. Ashgate.

- Hall, S. (1996). Who needs ‘identity’? In S. Hall & P. d. Gay (Eds.), Questions of cultural identity (pp. 1–17). Sage Publications.

- Heggen, K. (2008). Profesjon og identitet [Profession and identity]. In A. Molander & L. I. Terum (Eds.), Profesjonsstudier [The study of professions] (pp. 321–332). Universitetsforlaget.

- Holmberg, K. (2010). Musik- och kulturskolan i senmoderniteten: reservat eller marknad? [The community school of music and art in late modernity: Reservation or market?]. Malmö Academy of Music.

- Jordhus-Lier, A. (2015). Music teaching as a profession. On professionalism and securing the quality of music teaching in Norwegian municipal schools of music and performing arts. Nordic Research in Music Education, Yearbook Vol. 16 (pp. 163–182). Norwegian Academy of Music.

- Jordhus-Lier, A. (2018). Institutionalising versatility, accommodating specialists. A discourse analysis of music teachers’ professional identities within the Norwegian municipal school of music and arts [Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian Academy of Music]. Brage. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2480686

- Jordhus-Lier, A. (2021). Negotiating versatility and specialisation: On music teachers’ identification with subject positions in Norwegian municipal schools of music and performing arts. International Journal of Music Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761421989113

- Jørgensen, M. & Phillips, L. J. (2002). Discourse analysis as theory and method. Sage Publications.

- Karlsen, S. & Nielsen, S. G. (2020). The case of Norway: A microcosm of global issues in music teacher professional development. Arts Education Policy Review, 1–10. https.//doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2020.1746714

- Krüger, T. (1998). Teacher practice, pedagogical discourses and the construction of knowledge: Two case studies of teachers at work [Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison].

- Laclau, E. (1990). New reflections on the revolution of our time. Verso.

- Laclau, E. & Mouffe, C. (2001). Hegemony and socialist strategy towards a radical democratic politics. Verso.

- Mausethagen, S. (2013). Accountable for what and to whom? Changing representations and new legitimation discourses among teachers under increased external control. Journal of Educational Change, 14(4), 423–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-013-9212-y

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M. & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications.

- Ministry of Culture. (2009). Kulturløftet II.

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2014). Kulturskole [School of music and performing arts]. Retrieved 15.05.2015 from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/utdanning/grunnopplaring/artikler/kulturskole/id2345602/

- Molander, A. & Terum, L. I. (Eds.). (2008). Profesjonsstudier [The study of professions]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Mouffe, C. (2005). On The Political. Routledge.

- Nerland, M. (2004). Instrumentalundervisning som kulturell praksis. En diskursorientert studie av hovedinstrumentundervisning i høyere musikkutdanning [Instrumental teaching as cultural practice. A discourse oriented study of main instrument teaching in higher music education] [Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian Academy of Music]. https://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/029a10c127a62fe5aa987035fcb5f2a7?lang=no

- Neumann, I. B. (2001). Mening, materialitet, makt: En innføring i diskursanalyse [Meaning, materiality, power: An introduction to discourse analysis]. Fagbokforlaget.

- Norsk kulturskoleråd. (2003). På vei til mangfold. Rammeplan for kulturskolen [On the way to diversity. Curriculum for the municipal school of music and performing arts].

- Norsk kulturskoleråd. (2016). Mangfold og fordypning – rammeplan for kulturskolen [Diversity and in-depth learning – curriculum for the municipal school of music and performing arts]. https://www.kulturskoleradet.no/rammeplanseksjonen/rammeplanen

- Office of the Prime Minister. (2013). Political platform. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/a93b067d9b604c5a82bd3b5590096f74/politisk_platform_eng.pdf

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage Publications.

- Roberts, B. (2004). Who’s in the mirror? Issues surrounding the identity construction of music educators. Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education, 3(2).

- Stephens, J. (1995). Artist or teacher? International Journal of Music Education, os-25(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/025576149502500101

- Søreide, G. E. (2007). Narrative construction of teacher identity [Doctoral dissertation, University of Bergen]. BORA. https://hdl.handle.net/1956/2532

- Taylor, S. (2001a). Evaluating and applying discourse analytical research. In M. Wetherell, S. Taylor & S. J. Yates (Eds.), Discourse as data. A guide for analysis (pp. 311–330). Sage Publications.

- Taylor, S. (2001b). Locating and conducting discourse analytic research. In M. Wetherell, S. Taylor & S. J. Yates (Eds.), Discourse as data. A guide for analysis (pp. 5–48). Sage Publications.

- Tjora, A. (2017). Kvalitative forskningsmetoder i praksis. [Qualitative research methods in practice] 3. utg. Gyldendal Akademisk.

Fotnoter

- 1 In Norway, each municipality is obliged by law to run a school of music and performing arts or to collaborate with other municipalities in fulfilling that requirement. This is separate from the ordinary compulsory schools, which offer what one might call general music education. Attendance at the municipal school of music and performing arts is voluntary, and is, so to speak, an “extra”. In this article the term “school of music and arts” is used to refer to these municipal schools of music and performing arts. The term “compulsory school” is used to refer to the schools which all young people aged 6 to 16 have to attend (unless they go to one of the various alternative or independent schools in Norway, of which there are not very many).

- 2 In Norwegian: Utdanningsforbundet.