Introduction

Since 2017, generalist teacher education in Norway has consisted of a five-year integrated Master’s degree providing primary and lower secondary teacher education. A panel of international experts appointed to provide advice on the implementation of the new teacher education programme pinpointed the need for “collaboration across multiple stakeholders” as well as “the active agency of all participants in knowledge building and learning” (Advisory Panel for Teacher Education, 2020, pp. 26–27). This statement suggests that student teachers should take a more active role in shaping the new education programme. There is, however, a lack of awareness of who is recruited as a student teacher to the music subject within initial teacher education programmes. It is necessary to develop awareness of student teachers’ backgrounds, competence and ambitions in order to help facilitate student teachers’ learning as well as to actively involve them in the development of educational programmes. Knowing more about the student teachers is also essential from a systemic perspective. This includes knowing who is recruited to the music subject within teacher education, who is permitted to participate in the shaping of future generations by teaching music in schools, where do these student teachers come from, and what are their educational and musical preferences? Internationally, music education researchers have criticised music teacher education programmes for functioning as so-called “silos” (Väkevä et al., 2017) and reproducing musical values, beliefs and practices (Bowman, 2007; Gaunt & Westerlund, 2013; Sætre, 2014; Wright, 2019), thus possibly failing to prepare future music teachers for the diversity they will certainly meet later in their teaching careers. Finding out more about student teachers, then, is essential to addressing diversity and the (re)production of (in)equalities within teacher education music programmes.

This study is part of a larger research project1 exploring music as a study subject in the new five-year initial teacher education programme in Norway. In this article, we present the results from a quantitative cross-sectional survey mapping Norwegian generalist student teachers with a music specialisation, their perspectives on their current education and their ambitions and goals for becoming a generalist music teacher. The research questions guiding the study are: (1) Who are the generalist student teachers with a music specialisation in Norway? (2) What are the similarities and differences within this group of student teachers? (3) What are the possible implications for teacher education?

The first research question refers to the survey structure and provides information about the student teachers’ socio-economic, educational and musical background and their views on their current education, as well as their views on the subject of music in schools and their future work as music teachers in schools. The second research question pertains directly to our analysis, where identification of similarities and differences within the student group was essential. This analytical approach has been inspired by the theoretical grounding of this study, cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT), in which contradictions and tensions are considered driving forces for development and transformation (Cole & Engeström, 1993; Engeström, 2000, 2001, 2015; Sannino et al., 2016). Based on the survey results, we have constructed a portrait of the typical generalist student teacher with a music specialisation in Norway. This portrait feeds a discussion of the implications of the results for issues of diversity and inequality within generalist teacher education music (GTE music) programmes in Norway. Before presenting the results of our study, we will provide the readers with contextual information as well as information about our methodology.

The Norwegian context

Student teachers must choose between two specialised educational paths that provide different teaching qualifications: GLU2 1–7 for grades one to seven (lower and upper primary school) and GLU 5–10 for grades five to ten (upper primary and lower secondary school). Since 2017, Norwegian teacher education takes five years and includes an integrated Master’s degree with an extended specialisation and research approach related to students’ own practice. This new education format aims at improving subject knowledge, research and development competence within teacher education and the practice field, as well as professionalising teacher education by connecting theoretical and practical dimensions (Skagen & Elstad, 2020). The international expert panel providing advice to the Norwegian government on the implementation of this new format of teacher education notes that while the 2017 reform is consistent with broad international trends, it also stands out for its emphasis on “mutual efforts of higher education institutions, schools, municipalities, teacher unions, student teachers, and an array of national and international partners” (Advisory Panel for Teacher Education, 2020, p. 49). In other words, the student teachers are considered as important stakeholders who need to be involved in the shaping of the new type of Norwegian teacher education.

Upon finishing their GLU education, student teachers may move on to teach music in schools. There are no formal qualification requirements for teaching music in Norwegian primary schools (grades 1–7). Teaching music in lower secondary schools (grades 8–10), however, requires the teacher to have at least 30 ECTS3 of music. Music is a compulsory subject in all grades in Norwegian schools, although it is not very comprehensive in terms of annual teaching hours compared to other compulsory subjects. The Nordic countries are generally known for their progressive school music repertoires (Christophersen & Gullberg, 2017; Hebert, 2011; Karlsen & Väkevä, 2012; Nysæther & Schei, 2018; Wright, 2019), and popular music has been part of the Norwegian music curriculum since the 1970s (Ruud, 1996).

The music curriculum in Western schools has traditionally revolved around three areas – music-making, composing and listening (McCarthy, 2004) – which is also the case in Norway. In order to improve scores on Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests, the 2007 national curriculum incorporated basic skills such as reading, writing, arithmetic and digital skills in all school subjects. Holdhus and Espeland (2019) have previously identified the rationale for school music as being built on “instrumentalism, transmission of cultural works and values and individual creativity” (p. 97), while Fredriksen (2018) notes that the main focus of the Norwegian school music curriculum has apparently been on the musical experiences of the pupils. In August 2020, a new national curriculum was introduced in Norwegian primary and lower secondary school (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2019). This new national curriculum under implementation emphasises in-depth learning. Music as a subject is also expected, as are other subjects, to promote public health and life skills, as well as sustainability, democracy and citizenship. While retaining many of the structures in the music subject, a fourth musical core element has been added: cultural understanding. The intentions for this new curriculum was to be more practical, creative, critical and exploratory than the previous curriculum (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019 p. 19; The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2019). The new national curriculum thus suggests a broader context for education in general, as well as for the subject of music, thus creating new working conditions for the student teachers.

Previous research

Below we will briefly review previous research that is relevant to this particular study. The current study investigates the background, values and goals of generalist student music teachers. We will therefore combine knowledge obtained from research on teacher education, with insights generated by studies on the education of both generalist teachers and specialist music teachers.

Previous studies provide some awareness of the backgrounds of students in generalist teacher education in Norway. Studies show a predominance of female student teachers in Norway. In 2019, 74% of those in teacher education were women (OECD, 2019). In 1985, the ratio of women to men was 50:50 in teacher education in Norway, but since then, as in higher education in general, female students have predominated in teacher education (Aam et al., 2017). Furthermore, very few student teachers have an immigrant background. In fact, 94% of the male and 95% of the female student teachers in Norway reported not having an immigrant background in 2019 (Statistics Norway, 2019). Studies further show that student teachers obtained relatively good grades in upper secondary school, but that these are somewhat lower than those of students in traditional college education programmes4 (Aam et al., 2017). Ekren (2014) finds a high degree of connection between the parents’ social background and the child’s choice of education and their results. The connection between parent socio-economic status and child career choices (origin and destination) is also true of teacher education students: student teachers seem, based on analyses of their parents’ income and educational attainment, to have relatively the same level of education and socioeconomic status as their parents (Aam et al., 2017; Dahl, 2016). In other words, the majority of student teachers come from ethnically Norwegian middle-class families in which the parents also have a higher level of education.

We have found a solid body of international research reporting on teacher motivation5 that takes a variety of approaches conceptually and methodologically (see for example: Han et al., 2016; Richardson & Watt, 2006; Slemp et al., 2020). In this article, we concentrate on research related to student teachers. The rationale for researching student teacher motivation is described as being important in order to: (1) facilitate student teachers’ motivation in the design of teacher education programmes, (2) uncover what attracts individuals to pursue a teacher profession, (3) investigate how teacher motivation relates to pupil motivation, (4) apprehend how motivation is sustained over time, and, (5) understand the phenomena and conditions of pre- and in-service attrition (Fokkens-Bruinsma & Canrinus, 2014; Fredriksen, 2018; König & Rothland, 2012; Richardson & Watt, 2006; Sinclair, 2008).

Sinclair (2008) finds that motivation for teaching is connected to a positive self-evaluation of the student teacher’s own attributes and capabilities for working with children and to the intellectual stimulation that is expected from teaching. Fokkens-Bruinsma and Canrinus (2014) also find that working with children and adolescents provides an important motive for becoming a teacher. Roness and Smith (2009) find that student teachers’ personal experiences of teachers in their own schooling can inspire them to choose the teaching profession. It may be possible to draw a distinction between primary and lower secondary school student teachers: Book and Freeman (1986) find that the first group is more child-centred than the second group, which, in turn, is more subject-centred. It seems that altruistic and intrinsic motivation6 are helpful when choosing teaching as a profession, and essential if one opts to stay in the profession over time. Altruistically and intrinsically motivated student teachers seem to show higher levels of self-efficacy in their teaching, as well as to invest more effort in their studies (Bilim, 2014; Slemp et al., 2020) In the Norwegian context, Roness (2011) finds interest and altruism to be primary sources of motivation for student teachers and Nesje et al. (2018), find self-perception of teaching-related abilities and a desire to shape the future of children and adolescents, as well as an interest in teaching, to be motivating factors.

Student teacher identity has been addressed in several music education studies. There is a tendency for student music teachers to view themselves as either musicians or teachers (Bouij, 1998a, 1998b; Hargreaves et al., 2007; Pellegrino, 2009) and their perception of identity may relate to previous experiences of music (Ballantyne, 2006; Ballantyne & Zhukov, 2017). The development of teaching can be viewed as a three-step process. At the start of teacher training, the student is more self-focused, and towards the end of the programme, the student teachers pay more attention to the students (Killian et al., 2013). These findings are generally corroborated by music education research studies, which have found that student music teachers mainly identify as musicians and performers at the beginning of their education, but gradually develop a teacher identity over the course of their education (see for example Ballantyne et al., 2012; Georgii-Hemming & Westvall, 2010; Kenny, 2017; Kos, 2018). Furthermore, studies point to the inherent potential of music teacher education programmes to challenge and develop student teachers’ values and beliefs (Georgii-Hemming & Westvall, 2010; Kos, 2018), as well as to blend different identities, expertise and perceptions (Angelo & Georgii-Hemming, 2014; Ferm & Johansen, 2008; Heggen, 2008; Johansen, 2006; Kenny, 2017). Angelo and Georgii-Hemming (2014) believe that music education institutions fail if they do not provide students with an expanded professional knowledge of music and a qualified and sustainable language of reflection for discussing the knowledge base of music pedagogy, quality standards and key responsibilities. Georgii-Hemming et al. (2016) suggest that key methods for fostering student teacher’s professional knowledge include didactical reflection, case writing and research methods. Burnard and Holgersen (2016) also note that music teacher educators need to be role models.

According to Lowe et al. (2017), individual beliefs are related to self-regulation, as beliefs lead to actions that produce given outcomes and results. This way, the values and beliefs of the student teachers can shape music education practices in school, as well as affect the music teacher’s self-efficacy (Lowe et al., 2017). Furthermore, music teacher self-efficacy is increased through the teachers’ own involvement in and previous positive experiences of music, which helps create motivation in relation to the music teacher role (Garvis, 2008; Lowe et al., 2017). Self-efficacy is also associated with competence in disciplines that help to provide self-confidence and intrinsic motivation (Bandura, 2001; Garvis, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Sætre (2018) has found competence to be one of the most crucial factors in music teacher practice in Norwegian primary schools. Competence can be understood as having a broader repertoire of action, know-how and confidence in the classroom. Sætre’s (2014) study of teacher educators and their views on student teachers shows a perceived distinction between generalist and specialist student music teachers, in that specialists are perceived to be more proficient in music history and reading music than generalist student music teachers. Other studies have shown the importance of the music teacher’s own experience of mastery, and that a lack of such an experience can lead to resignation, anxiety and a lack of desire to teach the subject and, in the worst case, to attrition (Barrett et al., 2019; Fredriksen, 2018; Hennessy, 2017; Mäkinen & Juvonen, 2017). Some studies show that student teachers who practise music activities in their spare time and have music as a hobby also have a more positive attitude to teaching music in the classroom (Mäkinen et al., 2020; Mäkinen & Juvonen, 2017; Sætre et al., 2016). Hallam et al. (2009) found that the level of musical training provided to generalist teachers during their education affected their confidence, while Henley (2017) found that skills and competence acquired prior to initial education studies were very important for student music teachers’ confidence.

Research on the education of music teachers from a gender perspective is scarce; however, it is evident from previous research on music and gender in society that, in general, instrument selection is gendered: men play instruments and women sing (Lorentzen & Stavrum, 2007). Studies further show that choice of musical performance genre is gendered: men are typically involved in rock, heavy metal and instrumental jazz, while women are involved in vocal jazz, pop and are singer-songwriters (Björck, 2011a, 2011b; Lorentzen & Kvalbein, 2008; Nysæther & Schei, 2018; Ruud, 1996; Stavrum, 2004; Vinge, 1999). According to Stavrum (2008) and Lorentzen and Kvalbein (2008), men use music technology to a greater extent than women do. Gender differences and gender patterns in music are also maintained and continued in educational contexts in upper secondary and primary and lower secondary school (Kamsvåg, 2011; Marshall & Shibazaki, 2012; Onsrud, 2013) as well as in higher education (Borgen et al., 2010). One would expect that these findings are also true of student music teachers.

Cultural-historical perspectives

Our analysis is theoretically informed by cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT), and more specifically by Engeström’s (2015) theory of expansive learning. As a sub-study within a larger research project critically exploring music education practices in generalist teacher education, CHAT perspectives are well suited to this study, since CHAT is related to change and development.

CHAT positions the individual as a subject who takes part in communities and who develops their lifeworld through activity7 (Engeström, 2015). From this perspective, individuals cannot be separated from the objective world they are born into because it shapes them as human beings. The culture, history and artifacts of the life world condition the way that an individual can develop (Säljö, 2006). A key point from a CHAT perspective, however, is that individuals can transcend these boundaries by creating new objects and artifacts, thereby developing the culture they live in and (re)writing their own history (Cole & Engeström, 1993; Engeström, 1999a, 1999b; Sannino, 2015, 2016). Consequently, CHAT provides tools for understanding the actions and activities of individuals and groups, and thereby also provides a framework for understanding how subjects face crises and challenges and how they develop and adapt new tools and ways to interact – in other words, how they solve problems by learning collectively and expansively (Engeström, 2000, 2001, 2015; Sannino, 2015; Sannino et al., 2016).

Engeström’s (2001) five fundamental principles for activity theoretical framework have informed our analysis: (1) the activity system as the primary unit of analysis; (2) multivoicedness, i.e. different perceptions, intentions and points of view; (3) historicity; (4) contradictions, understood as latent tensions, as sources of change and development; and (5) the potential for expansive transformation (Engeström, 2000, 2001). We are aware that this study does not provide sufficient data to build a comprehensive picture of student teachers’ activity system. Our survey does, however, provide insight into the subjects and their historicity; in other words, where the student teachers come from, their history, how they look at their current situation and how they picture their future. Our further analysis will focus in particular on exploring multivoicedness and contradictions, thereby laying the groundwork for a discussion of the potential for development and change (Engeström, 2000, 2001, 2015).

Research design and methodology

This article reports on a mixed-methods PhD project designed as an explanatory sequential study (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). The first study in the project, which is reported in this article, is a quantitative cross-sectional survey (Fowler, 2009), which will be followed up with qualitative case studies. The survey provides broad statistical information about generalist student music teachers in Norwegian generalist teacher education, and its research purpose is primarily explorative and descriptive. This choice is backed by the theoretical and philosophical foundations of the study, requiring a critical approach to, and in-depth reflexive understanding of, complex activity systems in a dialectical world (Cole & Engeström, 1993; Engeström, 1999a, 1999b, 2015; Sannino, 2015, 2016). Therefore, the survey aims to map and describe the student teachers rather than test hypotheses statistically.

The population of the survey was defined as all active GLU student teachers in Norway between April and August 2020 who had music as one of their study specialisations. The population thus included student teachers from ten different higher education institutions who were in their first, second, third or fourth year of study, with a GLU 1–7 or GLU 5–10 specialisation. The total number of student teachers within this population at that time was 329, according to information gathered from department heads.

The survey questionnaire was developed in three stages. The first draft was sketched by the first author in accordance with the main aims and work plans of the FUTURED project. Secondly, the draft was discussed and revised in cooperation with the research team. Thirdly, the survey questionnaire was piloted qualitatively (Presser et al., 2004) with a group of 12 student teachers from one institution. The pilot gave valuable feedback on question formulations, usability, clarity and length and resulted in several minor revisions of the questionnaire (e.g. the addition of question 42). The survey was designed and distributed electronically using SurveyXact to email addresses gathered from the institutions.8 Finally, the first author sent several reminders to increase the response rate.

The final version of the questionnaire consisted of 49 questions covering six main themes: demographic background, musical training and work experience, musical background, digital tools, perceptions of study programmes and of music in schools, and future music teaching. The questionnaire (see Appendix 1) makes use of a range of answer formats (closed and open questions, scales, ranking and more) in accordance with the explorative and descriptive (but not explanatory) aims of the study.

The quantitative survey data was analysed mainly through the use of descriptive, univariate statistics (Ringdal, 2018), since the majority of the answer formats provide nominal data (Yang, 2010), which is reported below as a frequency or percentage. During the analytical process, however, it became evident that closer examination of certain sub-groups of respondents might be interesting (e.g. men and women) and additional bivariate analyses were conducted (e.g. gender distribution related to musical instruments and digital tools). Textual data was analysed in NVIVO in two main ways: basic quantitative content analysis (Miles & Huberman, 1994) and qualitative identification of categories within the body of textual data (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). The survey data was collected, managed and stored in accordance with data protection regulations and institutional guidelines.

A total of 214 student teachers responded to the questionnaire, a response rate of 65%. All ten initial teacher training institutions in Norway are represented. Of the respondents, 41% are GLU 1–7 students and 59% are GLU 5–10 students. All academic years (from 2017 to present) are represented (first year: 15%, second year: 36%, third year: 40% and fourth year: 7%). The results of the study should therefore be viewed as a fair representation of the population and of institutional and study year differences. However, the results of a survey study like this should be treated with caution, as a higher response rate might have altered the results in significant ways.

Results

Social, cultural and demographic background

61% of the respondents were female, 37% were male, and 2% chose to not respond. In GLU 1–7, the majority of respondents were female (76%) while 22% were male (2% chose to not answer). In GLU 5–10, the gender distribution was more equal: 51% were female and 48% were male. The age of the respondents ranged from 19 to 46. The majority of respondents were between 21 and 24 years of age (74%) and the mean age was 23.4 years.

Almost all respondents were born in Norway (96%), and only 6% identified themselves as a minority. Around 72% reported that both their mother and father had completed higher education. 52% had close family members (parents, siblings, grandparents) who were teachers, and 79% had close family members who worked with children, young people and adults in contexts such as music education (formal and informal), childcare and health. For the majority of respondents, music was a prominent part of their childhood and adolescence (96%). Most respondents had friends (94%) and family (76%) who sang or played an instrument. 30% reported that someone in their immediate family was a musician. 9 out of 10 respondents had access to musical instruments at home when they were growing up, and they all listened regularly to music at home to a large degree (82%) or to some degree (18%).

Musical training and work experience

When it comes to musical training, as many as 88% of respondents reported that their family provided and financed formal training in music (municipal school of music and performing arts: 73%, brass band: 43%, private lessons: 32%, music courses: 24%, religious settings: 22%). Half of the respondents had formal music education beginning in upper secondary school (32%) or at folk high schools (folkehøgskole) (20%). Some of the respondents studied music as part of higher education (3%). 46% reported, however, that they had no prior formal education in music.

96% had participated in informal learning settings, “the internet” and “self-taught” being the most reported categories (75% in both cases). The respondents had also learned about music from friends (57%) and family (55%), and half had participated in a rock or pop band. Less-reported informal settings include youth clubs (14%), learning music from computer games (8%) and organised meeting places (4%). In addition, 8% of the respondents mentioned religious settings such as musical worship activities. Only 4% reported not being active in any of these informal learning categories.

60% of the respondents had experience teaching in school or preschool (it is possible, however, that some of these are thinking of practicum9 experiences only), and 40% had worked with children in other contexts. 36% had taught music in formal educational contexts10 and 33% had worked as music instructors.11 28% of the respondents reported having worked with music in other ways, and 16% had professional experience as a musician. 62% of the respondents had been musically active for over ten years.

Musical profiles

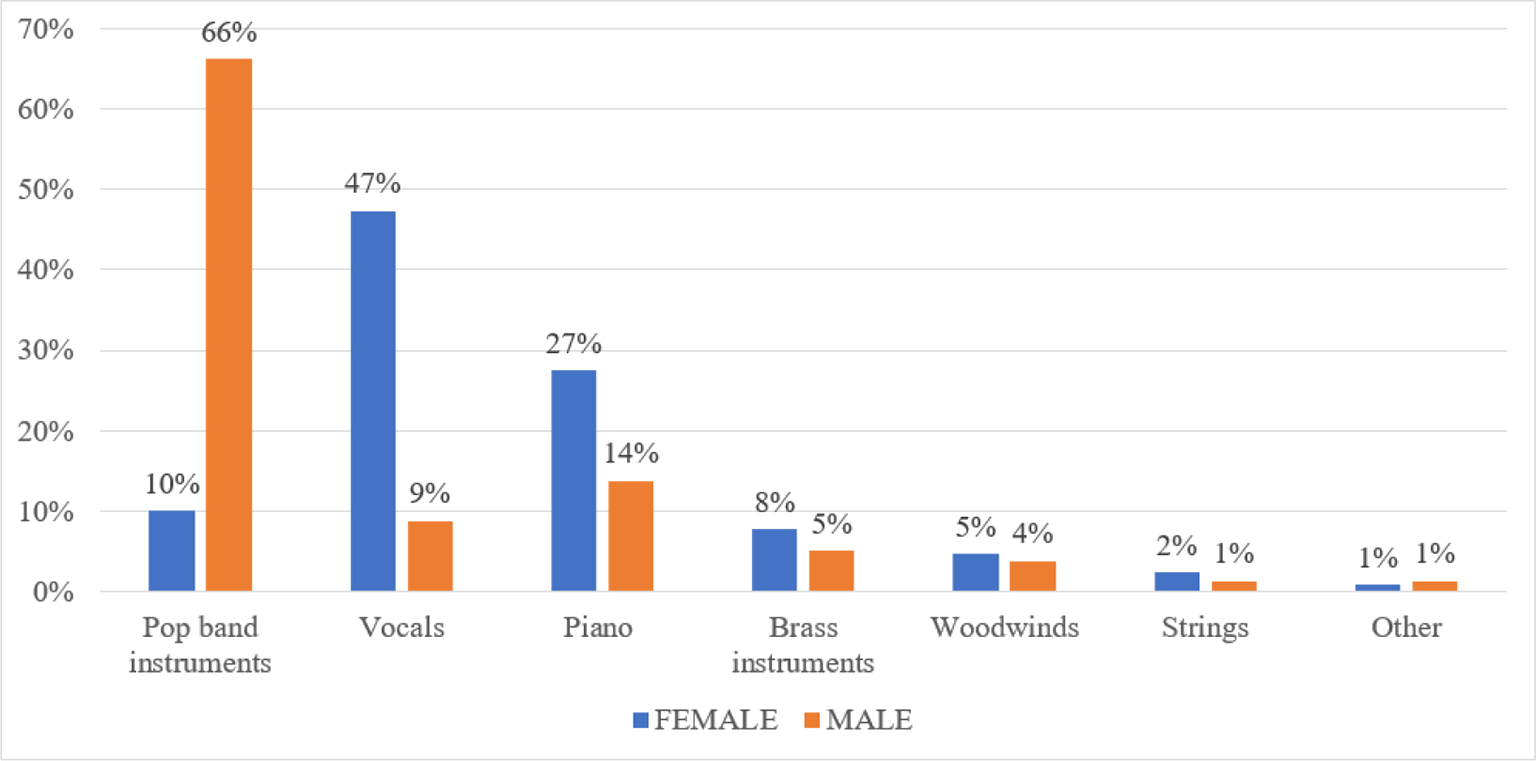

The respondents reported making music in a range of ways, including singing, electric instruments, percussion and drums, brass, woodwinds and string and chord instruments, and many reported playing more than one instrument. Top categories are vocals (33%), piano (23%), guitar (15%), electric guitar (6%) and electric bass (5%). Figure 1 displays the distribution of respondents according to instrument families, as well as gender distribution, which is very skewed in the case of pop band instruments and vocals.

The respondents reported performing in more than 38 different musical genres, the top five of which are pop (70%), rock (33%), classical (31%), jazz (29%) and singer-songwriter (29%). Two out of five wrote their own music and two-thirds improvised on their instrument. Furthermore, the respondents listened to music daily (82%) or several times a week (15%), and they listened to a range of musical styles as varied as those they perform. Pop is the most common genre (72%), followed by rock (46%), movie and game music (39%), jazz (38%) and hip hop (34%).

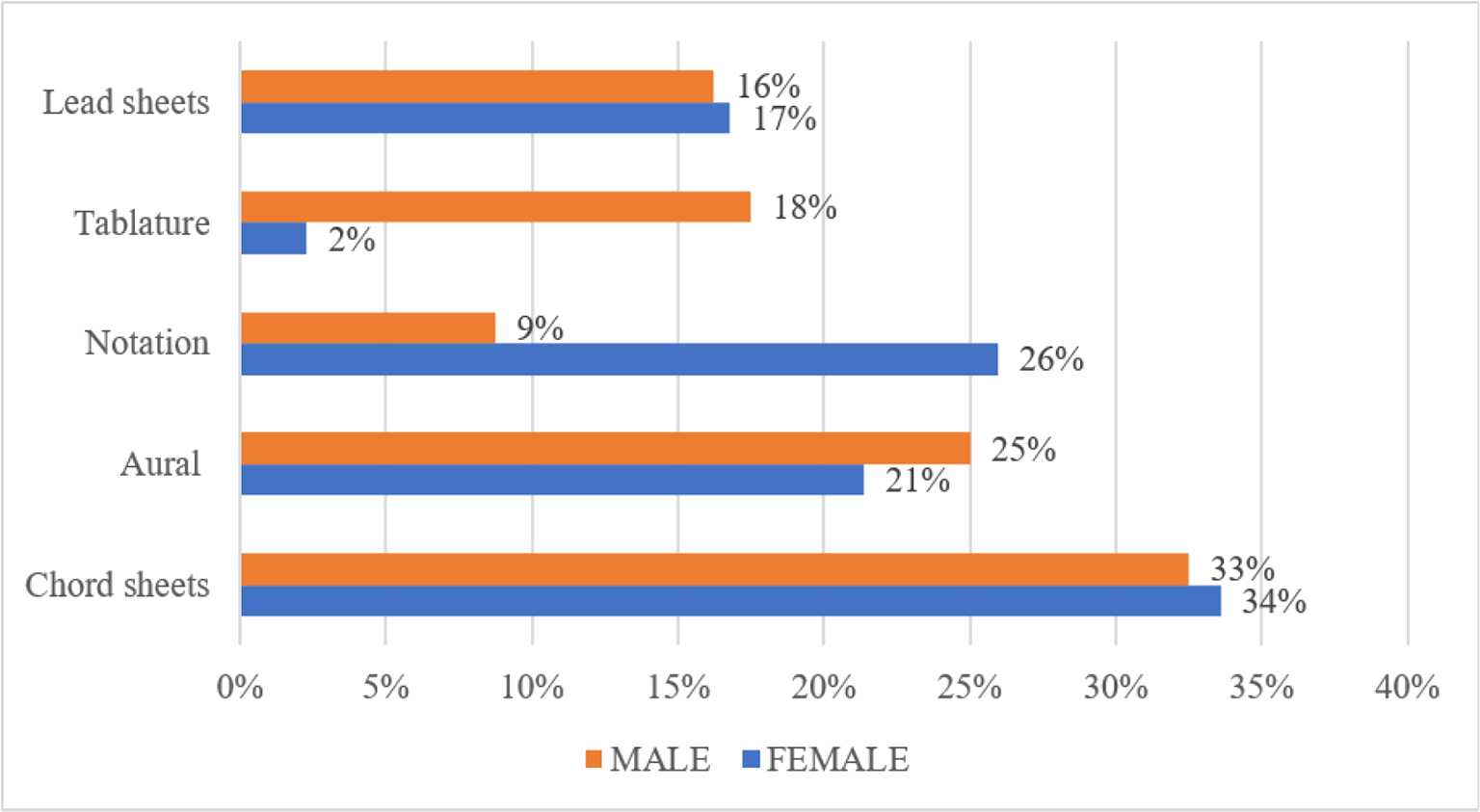

The respondents were further asked to use a three-point scale to evaluate the degree to which they had mastered reading tablature, chord/lead sheets and notation and learning songs by ear (survey question [SQ] 26). The respondents reported the highest level of competence in reading chord/lead sheets (only 8% reported little or no knowledge), followed by notation, learning songs by ear and reading tablature (15%, 21% and 35% had no or little knowledge, respectively). Respondents were also asked which approach they preferred (see Figure 2, which also shows the gender distribution).

Half of the respondents preferred a chord sheet approach (chord sheets: 34%, lead sheets: 16%), while 23% preferred an aural approach, 19% preferred notation and 8% preferred tablature. There are two notable differences when it comes to gender distribution. Significantly more women than men preferred notation, while more men than women preferred tablature.

Digital tools and competence

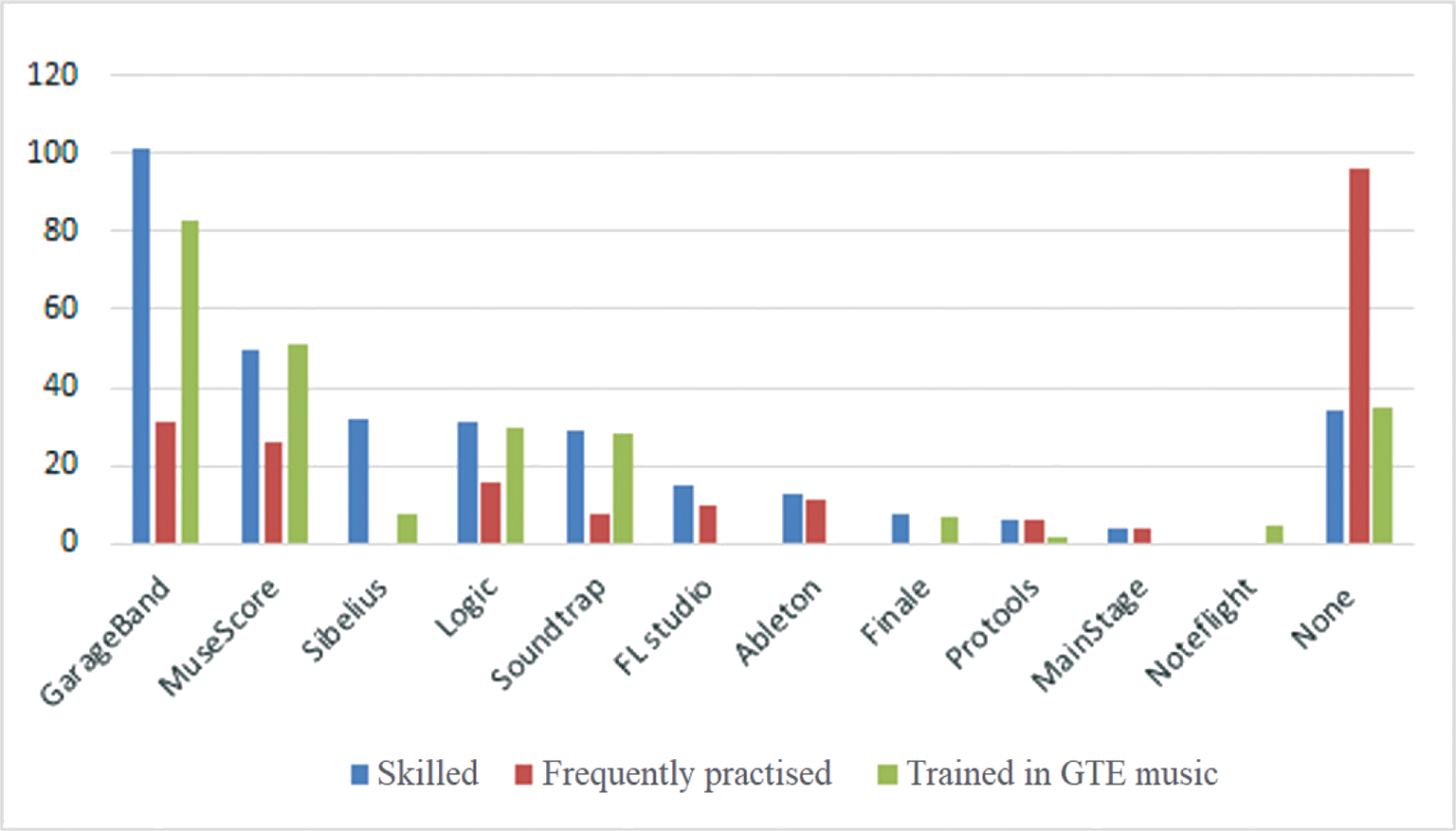

To explore the digital profiles of the student teachers, the survey included open-ended questions about which digital music tools they had mastered, which tools they used frequently, and which tools were used and taught in teacher education (see Figure 3).

The respondents seem to have had a fair level of knowledge and skills in a range of standard digital music tools. There seems to be a correspondence between the tools they reported as having mastered and the tools they had received training in in GTE music. While the results indicate that many of the student teachers were digitally skilled and used digital tools often, there was also a group of 96 respondents (45%) who in the open-ended question reported never using any digital music tools and 10,9% of the respondents reported having no skills in digital music tools. 14.1% of the respondents had no training in any digital music tools, but the open-ended answers suggest that they had not yet started those courses.

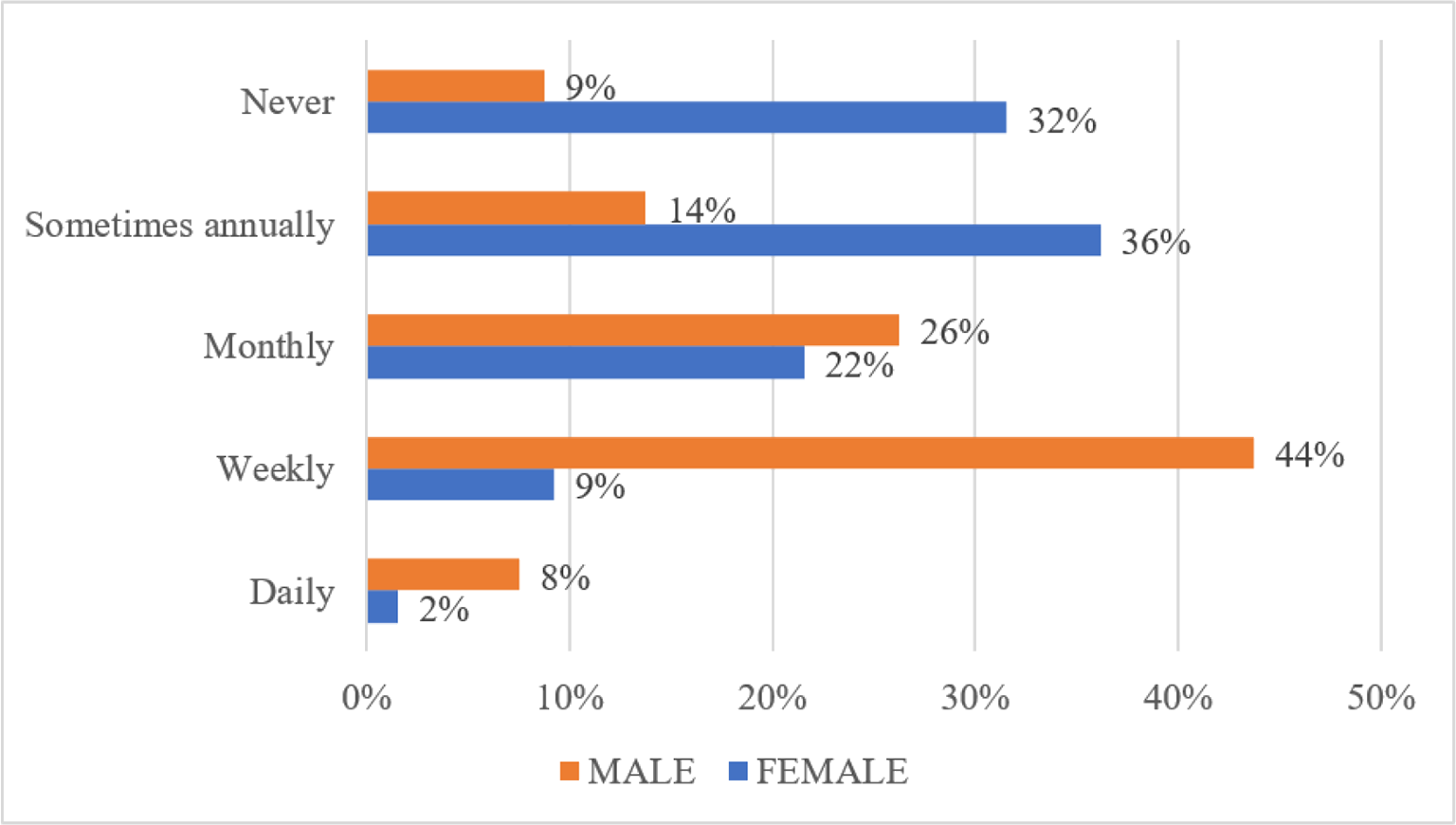

The survey continued with a five-point scale question (from “never” to “daily”) asking how often the respondents used digital music tools in general (i.e. not linked to any particular tool). Half of the respondents used digital tools a few times a year (28%) or monthly (23%), while others used digital tools weekly (22%) or daily (4%). Importantly, quite a large share of the respondents reported never using digital music tools (23%), which is in line with the results above. Moreover, the female respondents reported using such tools considerably less frequently than the male respondents. Figure 4 below demonstrates the gender differences in use of digital music tools.

As many as 32% of the females reported never using digital music tools, while only 8% of the males reported the same. 52% of the males used digital music tools weekly or daily, while females reported weekly or daily use to be around 11%.

Motivation and perceptions of GTE music

Until now, the focus has been on the respondents’ background. Now we turn to understanding them as present-day student teachers: Who are they when it comes to their motivation for applying to a GTE programme, and what do they think about music in GTE?

80% of the respondents reported (SQ36) what we may describe as a pupil-oriented motivation for applying to GTE (“I want to work with children”: 61%, and “I have always wanted to be a teacher”: 19%). In contrast, 10% reported a more content-oriented motivation; they wanted to work with music. The remaining respondents reported that their choice of education was random (7%) or unspecified (4%). 93 respondents elaborated on their motivation in SQ38. A broad categorisation of these answers strengthens the impression of pupil orientation: the largest group of answers (47) point to what we describe as an altruistic motivation (“I want to help pupils”, “I want to do something good for other people”, “I want to make a difference for pupils”). The second largest group of statements (33) concerns what we describe as intrinsic motivation (“I can work with something that interests me”, “I am meant to be a teacher”, “It motivates me”, “It is a calling”). Several wrote that having had really good teachers had motivated them to become teachers themselves. Only twelve related their motivation explicitly to the subject of music, and four focused on extrinsic factors such as reasonable work hours, a fair salary and long holidays. Of the 81% of the respondents who had undertaken one or more in-school practicum periods by the time of the survey (SQ39 and 40), 36% reported experiencing increased motivation as a result, 15% reported becoming less motivated, and 49% reported that their motivation did not change.

Several questions sought information about the student teachers’ perceptions of their study programmes. When it comes to musical acknowledgement, 11% of respondents felt that their musical competence received only a low degree of acknowledgement in their study programme (SQ37), while 59% reported some degree of acknowledgement and 31% reported a high degree. The respondents were also asked to rank the top three most important GTE music disciplines (SQ41 – see Table 1). The most important disciplines were music pedagogy and didactics12 (mean rank 2.8), playing together (samspill) (2.9) and arranging and composing (4.4), while the disciplines recognised as the least important were academic reading and writing (9.4), music history (7.6) and conducting and ensemble leadership (6.4). The cornerstone of much music education – instrumental and vocal lessons – is ranked number six by the group as a whole (mean rank 5.3).

| Rank | Ranking of GTE music disciplines | Rank | Ranking of ideal music teacher skills |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Music pedagogy and didactics | 1 | Classroom management and communication |

| 2 | Ensemble: playing together | 2 | Mentoring pupils in playing together and multi-voiced singing |

| 3 | Arranging and composing | 3 | Competence in playing one or more instruments |

| 4 | Aural training | 4 | Comprehension of cord/lead sheets & tablature |

| 5 | Music theory | 5 | Use of relevant music technology |

| 6 | Instrumental and vocal classes | 6 | Improvisation and aural skills |

| 7 | Music technology | 7 | Comprehension of musical notation |

| 8 | Conducting and ensemble management | 8 | Arranging and composition skills |

| 9 | Music history and genre knowledge | 9 | Mentoring pupils in dance activities |

| 10 | Academic reading and writing | 10 | Music history and genre knowledge |

The respondents’ ranking of ideal music teacher skills (SQ45) (see Table 1) puts classroom management and performative issues in the top three. Compared to the similar pattern found in the ranking of GTE music disciplines (SQ41), this underscores the respondents’ strong focus on both didactics/pedagogy and musical performance. The respondents were also asked whether any of the GTE music disciplines were unimportant to them. 87% answered “no”, and the 13% who answered “yes” identified academic reading and writing (21 respondents), music technology (6), music history (6), instrumental and vocal lessons (4), aural training (2), music theory and arranging (1) and arranging and composing (1) as not important to them in their education.

Finally, respondents were asked if they agreed or disagreed (on a six-point Likert scale) with 13 statements about their teacher education music programme (see SQ43). According to the results, the programmes are equally successful in most areas (nine items have means between 4.6 and 4.2, and the SD is between 1.1 and 1.4 for all 13 items), with creating commitment to the subject of music (mean 4.6) and pride in the teaching profession (4.5) at the top. Four issues stand out in the lower end of the scores. The programmes are least successful at developing critical reflection (4.0), taking the knowledge and preferences of the student teacher into account (3.8), preparing for diversity (3.8) and creating awareness of future challenges such as migration, globalisation, climate change and technology (3.4).

Nineteen respondents took the opportunity to elaborate on their views of the GTE music programmes (free text). Many respondents wrote that with no admission requirements in music, it was unclear what degree of prior musical competence the students should have. Some respondents had a high degree of musical competence, while others stated that they barely had any. Those without much musical competence called for more training in different musical disciplines. The respondents with a lot of musical experience criticised the programme for focusing too much on musical and performing aspects. Both groups agreed nevertheless that there is too little focus on didactics, teaching and teaching material adapted to different pupils and educational levels. Furthermore, some of the respondents thought that there are irrelevant disciplines within the GTE music programme, or that the programme contains too little pedagogical theory or too much reflection. There were also respondents who thought that the programme is relevant, developing and positive.

Perspectives on music in schools and future teaching

The respondents strongly believed (SQ44) that teaching is an important profession (mean 5.94, SD 0.42) and that music is an important part of pupils’ everyday school life (mean 5.44, SD 0.92). Most of the respondents also thought that teaching music is demanding (mean 5.07) and that there are too few music teaching hours in schools (mean 4.99). However, there was quite a lot of variation in these replies (SD 1.11 and 1.12).

The respondents were also asked (1) what the subject of music in schools should focus on the most (SQ46: choose the top three out of eleven predefined items), (2) to indicate what they will focus on as music teachers (SQ48: choose the top three out of eight items) and (3) what they would like their teaching to lead to (SQ49: choose the top three out of ten items). The top three items indicated for the first question (see Table 2) were: playing together in groups and bands (87%), pupil participation (54%) and making concerts, musicals and live performances (39%). This may reflect that the respondents view music in schools as being a practical, performance-oriented, pupil-oriented subject. The strong overall focus on playing together in groups and bands aligns with the high score for pupil participation and the focus on producing concerts (and it also aligns with the ratings for ideal music teacher skills – see Table 1). Other content-oriented topics such as singing, composing, music theory, music technology, dance and music history were included to a much lesser degree among the respondents’ top three choices.

| Subject focus | Percentage | Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Playing together in groups and bands | 87% | 185 |

| Pupil participation (pupils choose music and ways of working) | 54% | 115 |

| Making concerts, musicals, opera etc. | 39% | 83 |

| Listening to music, concerts, music video | 22% | 47 |

| Singing and vocal training | 21% | 45 |

| Composing and songwriting | 16% | 34 |

| Music theory and notation | 15% | 31 |

| Fostering pupils’ expertise in music technology | 14% | 30 |

| Dancing and choreography | 11% | 23 |

| Music history | 10% | 22 |

| Collaboration with other professional musicians | 4% | 8 |

The results from the second question (SQ48) reveal a similar tendency. The respondents as a group prioritised the pupil-centred category over content-oriented categories. The top choices were enhancing pupils’ creativity (77%), building on pupils’ everyday musical experiences (59%) and making music a vital part of pupils’ everyday lives (52%). Using pupils’ own music as a point of departure was, however, ranked considerably lower (27%), as was contributing to societal awareness of the pupils (23%). Of the more content-oriented items, contributing to pupils’ art experience was at the top (35%), while teaching pupils to play an instrument and teaching the classics13 were the least prioritised categories of all (19% and 3% respectively).

The pupil-oriented focus continues in the results of the third question (SQ49) (see Table 3). The items chosen the most concern giving pupils a feeling of mastery, joy in music, well-being and respite, and self-esteem and self-worth. Developing talent and passing on musical traditions were given much less priority by the respondents as a whole.

| Intended impact of music teaching | Percentage | Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Pupil sense of mastery | 83% | 158 |

| Pupil enjoyment of music | 74% | 141 |

| Pupil well-being and respite | 41% | 79 |

| Self-esteem and self-worth of pupils | 40% | 77 |

| Verification and support of pupils’ identity development | 29% | 56 |

| Building of cultural bridges | 11% | 21 |

| Pupil sense of recognition and being taken seriously | 10% | 19 |

| Space for critical reflection and debate | 5% | 10 |

| Talent development | 3% | 6 |

| Passing on of musical traditions | 3% | 5 |

Finally, the respondents were asked if they wished to work as music teachers in schools. 90% answered “yes” and 10% “no”. Of those answering “no” 15 were female and five were male (one of the respondents did not answer the gender question). The most common explanation provided was that they did not feel sufficiently competent and skilled to teach music (11 answers). Others referred to motivation: the music programme demotivated them (2), music is not interesting to teach (3), or they had a general lack of motivation for becoming a teacher (3). Other respondents explained that they would rather teach other subjects (2) or use music in other ways than by being a teacher (2).

The generalist student music teacher – a summary of characteristics

A major finding of this study is that generalist student music teachers appear strikingly similar in many ways. The majority of the student teachers are middle class, have Norwegian ethnicity and their immediate family works professionally with children and young people. Music has been a central part of their upbringing. They are motivated by the relational and performative aspects of teaching and learning and believe that the subject of music should focus on personal growth based on pupils’ own needs and interests. As future music teachers, they aim for pupils to experience mastery and discover the joy of music. Regarding their future as teachers in schools, the majority of student teachers want the subject of music to focus on performative music activities, with the aim of staging concerts, musicals and so on. The performative aspect seems to be perceived as valuable for its own sake. Overall, student teachers call for more attention on versatile methods for teaching music in the classroom.

Despite the similarities, there are also important differences between groups of respondents, particularly between genders. The specialisation of the typical male student teachers is GLU 5–10, which means that they would prefer to work in lower secondary school. The male student teachers typically play a pop band instrument and are interested in popular music styles, which is reflected in their preference for tablature, aural approaches and lead and chords sheets. The male student teachers rate themselves as skilled in digital music tools and use these tools more frequently than the majority of female student teachers.

The female student teacher has no clear preference in terms of specialisation (GLU 1–7 or GLU 5–10). The majority of female student teachers typically sing and play the piano, and they are occupied with a variety of styles but mostly popular and classical music. They prefer to use musical notation, notation with chord symbols and chord sheets to learn music. Female student teachers rate themselves as less skilled in digital music tools and use such tools far less frequently than the majority of the male student teachers.

Nevertheless, their music teaching values seem to be the same. Although the males and females have different skills, experience and preferences, both genders have a common vision of the ideal music teacher and share the same values and beliefs with respect to what is most important in the practice of music teaching in schools.

Discussion

This article began by asking who the student teachers in GTE music are, and our survey has shed light on this question. More specifically, our survey has helped generate a portrait of the majority of the students, that is, of the typical male student and the typical female student, within the music programme for generalist teacher education. From a CHAT perspective, the student portrait represents the majority of the students as subjects within the activity context of music teacher education. The temporal ordering of the questions and replies (background/history, teacher education/present and prospective teacher practice/future) has given the analysis and the results historicity. The current quantitative sub-study also provides information about certain characteristics of the teacher education activity system. Further qualitative examination is therefore required in order to explore trends in the data material and to provide a richer and more nuanced picture of generalist student music teachers in Norway. Below, we will discuss the results and their implications, thereby identifying issues for further exploration. In doing so, we will draw upon a similar study, namely the study by Sætre (2014) of generalist music teacher educators, representing a related group of subjects within the same activity context.

The student demographics in this study are consistent with the findings of other studies: choice of career seems to be connected to family background, and parents appear to be mostly middle class (see for example Aam et al., 2017; Dahl, 2016). While not directly comparable, the results from our study mirror those of other studies, showing that very few student teachers come from a cultural minority background (Statistics Norway, 2019). In other words, student teachers within the GTE music programme have similar cultural and socio-economic backgrounds.

It is interesting that classical music seems to be of less importance than popular music genres for Norwegian music student teachers. Even for the classically trained student teachers, popular music seems to be of higher value and relevance. However, popular music is very widespread and may even have a hegemonic position in the Nordic countries (Christophersen & Gullberg, 2017).

The students’ vision of the role of the ideal music teacher represents the object of the students’ activity in teacher education from a CHAT perspective. We would like to highlight a few of the results from the section of the survey enquiring about teacher roles and identity, as they demonstrate interesting tendencies.

Although some of the respondents demonstrate intrinsic motivation in their career choice, most of them report altruistic motives, such as wanting to make a difference for children. These findings corroborate previous Norwegian studies (see Nesje et al., 2018; Roness, 2011; Roness & Smith, 2009). It is not surprising, then, that the respondents’ replies show a clear desire for a greater pedagogical/didactical focus in the GTE music programme. However, the results also show a divide: Between the performative and pedagogical side of music on the one hand, and, on the other hand, between practical/performative and theoretical aspects of music. Thus, in some respects, the student teachers resemble their educators.

Sætre (2014) found tensions between teacher and musician identities, as well as between practical activities and research among music teacher educators. The performance-oriented conservatoire discourse seemed to prevail, resulting in the maintenance of a vast breadth of musical disciplines “rather than focusing on ‘what is needed in schools’” (Sætre, 2014, p. 214). The students’ teacher identities as established in this study bear the hallmark of both the generalist and the specialist music teacher, understood as “teachers who know music” and “musicians who also teach” (Aróstegui & Kyakuwa, 2021, p. 20). This distinction is, however, less clear than in other studies (see Aróstegui & Kyakuwa, 2021; Ballantyne, 2006; Ballantyne et al., 2012; Bouij, 1998b). In other words, the current generation of Norwegian GTE music student teachers seem to be pupil-centred and to perceive teaching as a calling, while also being musically competent and performance-oriented. The respondents’ call for a more relevant didactical/pedagogical focus may be a starting point for negotiation in a further development process in generalist music teacher education.

The new national curriculum in Norway (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2019) puts emphasis on the practical and performative side of the subject of music. From a school music point of view, then, these future teachers represent a positive contribution to promoting music as a practical, creative and performance subject for pupils in schools. However, from the point of view of teacher education, our study shows possible consequences from the performative focus. Some of the respondents reported experiencing a lack of competence in instrumental skills, as well as having difficulty playing in a group. Sætre (2014) found a traditional understanding of competence within generalist music teacher education, where instrumental skills, playing together, music theory and practical music were considered essential. The inherent practical and performative focus on music in compulsory schools as well as in generalist music teacher education requires students to be practically skilled in music and, as our study shows, not all of them feel competent in this respect.

Viewing the results through a CHAT lens, the musical interests and skills that the student teachers acquired and cultivated before entering teacher education are essential tools (Cole & Engeström, 1993; Engeström, 2015; Säljö, 2006) that they bring into the teacher education activity system. Our results also show that student teachers, including cultural minority students, come from families with musical interests, and that their families have enabled them to pursue their musical interests by providing music training. For example, three out of four respondents in this study attended municipal schools of music and performing arts, which recruit mainly from the middle-class population (Berge et al., 2019; Bjørnsen, 2012; Gustavsen & Hjelmbrekke, 2009). These schools are also characterised by a gender imbalance regarding both general recruitment and choice of instrument (Berge et al., 2019). Our study thus aligns with the findings of studies that demonstrate choice of instrument and preferred genre to be gendered (Björck, 2011a, 2011b; Lorentzen & Kvalbein, 2008; Stavrum, 2004, 2008). The results of our study also correspond with other studies showing that when specialisation in musical roles and practices in popular music genres is voluntary, personal choices are influenced by conventions and gender norms (Kamsvåg, 2011; Nysæther & Schei, 2018; Onsrud, 2013).

Our findings also support previous studies that indicate that student teachers benefit from previous musical competence (Henley, 2017; Lowe et al., 2017). Previous research has shown that music teachers’ experience of mastery is an important issue (Barrett et al., 2019; Hennessy, 2017; Mäkinen & Juvonen, 2017). According to Henley (2017), skills and competence acquired prior to initial teacher education are very important for student music teachers’ confidence. While the respondents of this study universally preferred popular music styles and found playing together in groups and bands to be a core activity in schools, the female student teachers have considerably less experience in these activities than their fellow male student teachers do. While typical female choices of instrument such as piano and vocals require little technological expertise beyond the musical performance itself, typically “masculine” pop band instruments require the ability to handle amplifiers, gadgets, stomp boxes, cables and other sound equipment in addition to mastering the actual instrument. As expressed in an open-ended response by a female student teacher who is highly experienced musically and classically trained: “I feel like I have pretty narrow skills when it comes to instruments. I’ve mastered very few instruments (voice, piano and saxophone) compared to what I should have done in order to face the great diversity in schools.” (SQ43.1)

The results from this study indicate that certain competences and skills are favoured within music in GTE, and that mastering specific instruments, methods and technologies may be particularly beneficial to student teachers. Together with Sætre’s (2014) study, we suggest a possible gap between formal requirements for entrance into a generalist music teacher programme and the competences and skills that students are expected to learn and master during the course of their education. Our results also suggest a need to critically discuss what should be considered essential competence within generalist music teacher education, especially when considering the implications for diversity. The student teachers’ musical background, which adds to their competence, seems largely to be acquired outside of compulsory schooling and in settings that are already characterised by skewed recruitment and a lack of diversity. This picture is further complicated by issues of gender and cultural identity. Our findings suggest that generalist teacher education music programmes repeat certain patterns of inequality found in both generalist teacher education and in the cultural sector in general.

Concluding remarks

Not only are the respondents strikingly similar to each other, they also resemble their educators in some respects. Based on our data, we cannot say whether the similarities between student teachers and educators are due to socialisation or recruitment processes – i.e. whether the student teachers’ attitudes and opinions develop during their education, or if the GTE music programme attracts certain types of students. However, the findings of this study suggest a lack of diversity among our respondents that to a certain degree mirrors other areas of society. The similarities between student teachers and between student teachers and their educators does suggest a possible reproduction of values and beliefs within generalist music teacher education programmes.

From a CHAT perspective, contradictions and multivoicedness are seen as driving forces for development and transformation (Engeström, 2001), both on an individual and a systemic level. When envisioning the ideal music education within schools, student teachers and educators seem to share some common values and beliefs about the performative side of music as a subject, which may lead to an undisputed cultural practice within generalist music teacher education that reproduces a narrow perception of music teaching and also mirrors issues of inequality in other fields of society. Consensus and lack of diversity among student teachers and within the GTE music programme may therefore be considered problematic from the perspective of transformation and development (Cole & Engeström, 1993; Engeström, 2015). However, student teachers and teacher educators do not share the same perspectives on which tools the GTE music programme should provide. Student teachers call for methodological and musical didactic tools, while the educators seem to emphasise their specialised subject matter of music knowledge and performance, often originating from a conservatory culture (Sætre, 2014). Issues concerning this narrow perspective supports Kos’ (2018) argument that the music educator’s responsibility for exploring and challenging values and beliefs is important for broadening students’ views. Informed by CHAT, we suggest negotiations between the two subjects – teacher educators and student teachers – to expand the perspective and practical outcomes of future music teachers in school (Engeström, 1999a, 1999b, 2001, 2015; Sannino et al., 2016). We suggest that expanded professional knowledge (Angelo & Georgii-Hemming, 2014; Georgii-Hemming et al., 2016) can serve as a potential shared object for negotiation in generalist music teacher education.

Change in a static activity can be driven by external influences, such as curriculum change, new demands from a knowledge society or changed policies, but the risk of resistance and fallback in such cases is very likely (Engeström, 1999b, 2015; Sannino, 2015). However, when the need for change is identified and fuelled by participants within the activity, internal initiatives and commitment to the developmental process can potentially lead to expansive learning and transformation that are sustained over time (Engeström, 2015). In other words, if the GTE music programme creates openings and equal premises for negotiations between teacher educators and student teachers (and other participants), latent tensions and contradictions can become fertile sources for change through critical reflection and actions of transformative agency (Sannino, 2015; Sannino et al., 2016).

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Norwegian Research Council and developed within the research project “Music Teacher Education for the Future” (FUTURED 2019–2022).

References

- Aam, P., Bakken, P., Kvistad, E., & Snildal, A. (2017). A brief introduction to primary and lower secondary teacher education in Norway. Advisory Program in Teacher Education. https://www.nokut.no/globalassets/nokut/rapporter/ua/2017/a-brief-introduction-to-norwegian-pls_2017.pdf

- Advisory Panel for Teacher Education, A. (2020). Transforming Norwegian teacher education: The final report for the International Advisory Panel for Primary and Lower Secondary Teacher Education (3-2020). https://www.nokut.no/globalassets/nokut/rapporter/ua/2020/transforming-norwegian-teacher-education-2020.pdf

- Angelo, E., & Georgii-Hemming, E. (2014). Profesjonsforståelse: En innfallsvinkel til å profesjonalisere det musikkpedagogiske yrkesfeltet. In S.-E. Holgersen, E. Georgii-Hemming, S. G. Nielsen, & L. Väkevä (Eds.), Nordic Research in Music Education. Yearbook Vol. 15 (pp. 25–47). NMH-publikasjoner.

- Aróstegui, J. L., & Kyakuwa, J. (2021). Generalist or specialist music teachers? Lessons from two continents. Arts Education Policy Review, 122(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2020.1746715

- Bakar, A. R., Mohamed, S., Suhid, A., & Hamzah, R. (2014). So you want to be a teacher: What are your reasons? International Education Studies, 7(11). https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n11p155

- Ballantyne, J. (2006). Reconceptualising preservice teacher education courses for music teachers: The importance of pedagogical content knowledge and skills and professional knowledge and skills. Research Studies in Music Education, 26(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103x060260010101

- Ballantyne, J., Kerchner, J. L., & Aróstegui, J. L. (2012). Developing music teacher identities: An international multi-site study. International Journal of Music Education, 30(3), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761411433720

- Ballantyne, J., & Zhukov, K. (2017). A good news story: Early-career music teachers’ accounts of their “flourishing” professional identities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 68, 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.009

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Barrett, M. S., Zhukov, K., & Welch, G. F. (2019). Strengthening music provision in early childhood education: A collaborative self-development approach to music mentoring for generalist teachers. Music Education Research, 21(5), 529–548.

- Berge, O. K., Angelo, E., Torvik, M. H., & Emstad, A. B. (2019). Kultur + skole = sant. Kunnskapsgrunnlag om kulturskolen i Norge. https://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/finn-forskning/rapporter/evaluering-av-kulturskolen/

- Bilim, I. (2014). Pre-service elementary teachers’ motivations to become a teacher and its relationship with teaching self-efficacy. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 152, 653–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.09.258

- Björck, C. (2011a). Claiming space: Discourses on gender, popular music, and social change. Academy of Music and Drama.

- Björck, C. (2011b). Freedom, constraint, or both? Readings on popular music and gender. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 10(2), 8–31.

- Bjørnsen, E. (2012). Inkluderende kulturskole. Utredning av kulturskoletilbudet i storbyene (5/2012). Agderforskning. http://docplayer.me/3887192-Inkluderende-kulturskole.html

- Book, C. L., & Freeman, D. J. (1986). Differences in entry characteristics of elementary and secondary teacher candidates. Journal of Teacher Education, 37(2), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/002248718603700209

- Borgen, J. S., Arnesen, C. Å., Caspersen, J., Gunnes, H., Hovdhaugen, E., & Næss, T. (2010). Kjønn og musikk: Kartlegging av kjønnsfordelingen i utdanning og arbeidsliv innenfor musikk. (Report no. 49/2010). NIFU. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/279649

- Bouij, C. (1998a). Musik-mitt liv och kommande levebröd. En studie i musiklärares yrkessocialisation. University of Gothenburg.

- Bouij, C. (1998b). Swedish music teachers in training and professional life. International Journal of Music Education, (1), 24–32.

- Bowman, W. (2007). Who is the “We”? Rethinking professionalism in music education. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 6(4), 109–131.

- Burnard, P., & Holgersen, S.-E. (2016). Different types of knowledges forming professionalism: A vision of post-millennial music teacher education. In P. Bernard & E. Georgii-Heming (Eds.), Professional knowledge in music teacher education (pp. 180–192). Routledge.

- Christophersen, C., & Gullberg, A.-K. (2017). Popular music education, participation and democracy: Some Nordic perspectives. In G. D. Smith, Z. Moir, M. Brennan, P. Kirkman, & S. Rambarran (Eds.), The Routledge research companion to popular music education (pp. 425–437). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315613444-33

- Cole, M., & Engeström, Y. (1993). A cultural-historical approach to distributed cognition. In G. Salomon (Ed.), Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational considerations (pp. 1–46). Cambridge University Press.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Dahl, T. (2016). Om lærerrollen: Et kunnskapsgrunnlag. Fagbokforlaget.

- Ekren, R. (2014). Sosial reproduksjon av utdanning? Samfunnsspeilet, 5. https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/_attachment/210120?_ts=14a1afdd738

- Engeström, Y. (1999a). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. Perspectives on activity theory, 19(38), 19–30.

- Engeström, Y. (1999b). Introduction. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R.-L. Punamäki-Gitai (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 1–16). Cambridge University Press.

- Engeström, Y. (2000). Udviklingsarbejde som uddannelsesforskning: Ti års tilbageblik og et blik ind i zonen for den nærmeste udvikling. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Tekster om læring (pp. s. 270–283). Roskilde Universitetsforlag.

- Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747

- Engeström, Y. (2015). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Ferm, C., & Johansen, G. (2008). Professors’ and trainees’ perceptions of educational quality as related to preconditions of deep learning in musikdidaktik. British Journal of Music Education, 25(2), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0265051708007912

- Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & Canrinus, E. T. (2014). Motivation for becoming a teacher and engagement with the profession: Evidence from different contexts. International Journal of Educational Research, 65, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2013.09.012

- Fowler, F. J. (2009). Survey research methods (4th ed.). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230184

- Fredriksen, B. (2018). Leaving the music classroom: A study of attrition from music teaching in Norwegian compulsory schools. Norwegian Academy of Music.

- Garvis, S. (2008). Teacher self-efficacy for the arts education: Defining the construct. Australian Journal of Middle Schooling, 8(1), 25–31.

- Gaunt, H., & Westerlund, H. (2013). Collaborative learning in higher music education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315572642

- Georgii-Hemming, E., Burnard, P., & Holgersen, S.-E. (2016). Professional knowledge in music teacher education. Routledge.

- Georgii-Hemming, E., & Westvall, M. (2010). Teaching music in our time: student music teachers’ reflections on music education, teacher education and becoming a teacher. Music Education Research, 12(4), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2010.519380

- Gustavsen, K., & Hjelmbrekke, S. (2009). Kulturskole for alle? https://openarchive.usn.no/usn-xmlui/handle/11250/2439305

- Hallam, S., Burnard, P., Robertson, A., Saleh, C., Davies, V., Rogers, L., & Kokatsaki, D. (2009). Trainee primary-school teachers’ perceptions of their effectiveness in teaching music. Music Education Research, 11(2), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800902924508

- Han, J., Yin, H., & Boylan, M. (2016). Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1217819. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2016.1217819

- Hargreaves, D. J., Purves, R. M., Welch, G. F., & Marshall, N. A. (2007). Developing identities and attitudes in musicians and classroom music teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(3), 665–682. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X154676

- Hebert, D. G. (2011). Originality and institutionalization: Factors engendering resistance to popular music pedagogy in the USA. Music Education Research International, 5, 12–21.

- Heggen, K. (2008). Profesjon og identitet. In A. Molander, & L. I. Terum (Eds.), Profesjonsstudier (pp. 321–332). Universitetsforlaget.

- Henley, J. (2017). How musical are primary generalist student teachers? Music Education Research, 19(4), 470–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1204278

- Hennessy, S. (2017). Approaches to increasing the competence and confidence of student teachers to teach music in primary schools. Education 3-13, 45(6), 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2017.1347130

- Holdhus, K., & Espeland, M. (2019). Music in future Nordic schooling. European Journal of Philosophy in Arts Education (EJPAE), 2(2), 85–118. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3383789

- Johansen, G. (2006). Fagdidaktikk som basis- og undervisningsfag. Bidrag til et teoretisk grunnlag for studier av utdannigskvalitet. In F. V. Nielsen, & S. Graabræk Nielsen (Eds.), Nordic Research in Music Education. Yearbook Vol. 8 (pp. 115–136). NMH-publikasjoner.

- Kamsvåg, G. A. (2011). Tredje time tirsdag. Musikk: En pedagogisk-antropologisk studie av musikkaktivitet og sosial organisasjon i ungdomsskolen. Norges musikkhøgskole.

- Karlsen, S., & Väkevä, L. (2012). Future prospects for music education: Corroborating informal learning pedagogy. Cambridge Scholars Publisher.

- Kenny, A. (2017). Beginning a journey with music education: Voices from pre-service primary teachers. Music Education Research, 19(2), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2015.1077801

- Killian, J. N., Dye, K. G., & Wayman, J. B. (2013). Music student teachers. Journal of Research in Music Education, 61(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429412474314

- Kos, R. P. (2018). Becoming music teachers: preservice music teachers’ early beliefs about music teaching and learning. Music Education Research, 20(5), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2018.1484436

- Künzli, R. (2000). German Didaktik: Models of re-presentation, of intercourse, and of experience. In I. Westbury, S. Hopmann & K. Riquarts (Eds.), Teaching as a reflective practice (pp. 41–54). Routledge.

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Sage.

- König, J., & Rothland, M. (2012). Motivations for choosing teaching as a career: Effects on general pedagogical knowledge during initial teacher education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 289–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2012.700045

- Lorentzen, A., & Kvalbein, A. (2008). Musikk og kjønn – i utakt? Norsk kulturråd / Fagbokforlaget.

- Lorentzen, A. H., & Stavrum, H. (2007). Musikk og kjønn: Status i felt og forskning (TF-paper no. 5/2007). Telemarksforskning-Bø.

- Lowe, G. M., Lummis, G. W., & Morris, J. E. (2017). Pre-service primary teachers’ experiences and self-efficacy to teach music: Are they ready? Issues in Educational Research, 27(2), 314–329.

- Marshall, N. A., & Shibazaki, K. (2012). Instrument, gender and musical style associations in young children. Psychology of Music, 40(4), 494–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735611408996

- McCarthy, M. (2004). Toward a global community: The international society for music education. International Society for Music Education.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2019). Skaperglede, engasjement og utforskertrang: Praktisk og estetisk innhold i barnehage, skole og lærerutdanning. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/skaperglede-engasjement--og-utforskertrang/id2665820/

- Mäkinen, M., Eronen, L., & Juvonen, A. (2020). Does curriculum change have impact in students? A comparative research of teacher students’ willingness to teach music. The Changing Face of Music and Art Education, 10, 21–58.

- Mäkinen, M., & Juvonen, A. (2017). Can I survive this? Future class teachers’ expectations, hopes and fears towards music teaching. Problems in Music Pedagogy, 16(1), 49.

- Nesje, K., Brandmo, C., & Berger, J.-L. (2018). Motivation to become a teacher: A Norwegian validation of the factors influencing teaching choice scale. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(6), 813–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1306804

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2019). Læreplan i musikk. https://www.udir.no/lk20/mus01-02

- Nysæther, E. T., & Schei, T. B. (2018). Empowering girls as instrumentalists in popular music. Studying change through Engeström’s cultural-historical activity theory. In F. Pio, A. Kallio, Ø. Varkøy, & O. Zandén (Eds.), Nordic Research in Music Education. Yearbook Vol. 19 (pp. 75–96). NMH-publikasjoner.

- OECD. (2019). OECD TALIS study Initial Teacher Preparation 2015–2017 (Country Background Report Norway). https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/0f4d861825c840cd88958023a844ed3b/final-121016-new-summary-cbr-norway1108292.pdf

- Onsrud, S. V. (2013). Kjønn på spill – kjønn i spill: En studie av ungdomsskoleelevers musisering. Universitety of Bergen.

- Pellegrino, K. (2009). Connections between performer and teacher identities in music teachers: Setting an agenda for research. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 19(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083709343908

- Presser, S., Couper, M. P., Lessler, J. T., Martin, E., Martin, J., Rothgeb, J. M., & Singer, E. (2004). Methods for testing and evaluating survey questions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 68(1), 109–130.

- Richardson, P. W., & Watt, H. M. G. (2006). Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian universities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660500480290

- Ringdal, K. (2018). Enhet og mangfold: Samfunnsvitenskapelig forskning og kvantitativ metode (4th ed.). Fagbokforlaget

- Roness, D. (2011). Still motivated? The motivation for teaching during the second year in the profession. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 628–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.10.016

- Roness, D., & Smith, K. (2009). Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) and student motivation. European Journal of Teacher Education, 32(2), 111–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760902778982

- Roness, D., & Smith, K. (2010). Stability in motivation during teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 36(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607471003651706

- Ruud, E. (1996). Musikk og verdier: Musikkpedagogiske essays. Universitetsforlaget.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

- Sannino, A. (2015). The emergence of transformative agency and double stimulation: Activity-based studies in the Vygotskian tradition. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 4, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2014.07.001

- Sannino, A. (2016). Double stimulation in the waiting experiment with collectives: Testing a Vygotskian model of the emergence of volitional action. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 50(1), 142–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9324-4

- Sannino, A., Engeström, Y., & Lemos, M. (2016). Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 25(4), 599–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2016.1204547

- Sinclair, C. (2008). Initial and changing student teacher motivation and commitment to teaching. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 36(2), 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660801971658

- Skagen, K., & Elstad, E. (2020). Lærerutdanningen i Norge. In E. Elstad (Ed.), Lærerutdanning i nordiske land (pp. 120–138). Universitetsforlaget.

- Slemp, G., Field, J., & Cho, A. (2020). A meta-analysis of autonomous and controlled forms of teacher motivation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103459

- Statistics Norway. (2019). Studenter i høyere utdanning i Norge og i utlandet. https://www.ssb.no/utuvh

- Stavrum, H. (2004). «Syngedamer» eller jazzmusikere? Fortellinger om jenter og jazz. Høgskolen i Telemark.

- Stavrum, H. (2008). Kjønnede relasjoner innenfor rytmisk musikk: Hva vet vi, og hva bør vi vite? In A. Lorentzen & A. Kvalbein, (Eds.), Musikk og kjønn i utakt? (pp. 59–76). Norsk kulturråd / Fagbokforlaget.

- Säljö, R. (2006). Læring og kulturelle redskaper: Om læreprosesser og den kollektive hukommelsen (S. Moen, Trans.). Cappelen Akademisk Forlag.

- Sætre, J. H. (2014). Preparing generalist student teachers to teach music: A mixed-methods study of teacher educators and educational content in generalist teacher education music courses Norwegian Academy of Music.

- Sætre, J. H. (2018). Why school music teachers teach the way they do: A search for statistical regularities. Music Education Research, 20(5), 546–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2018.1433149

- Sætre, J. H., Neby, T. B., & Ophus, T. (2016). Musikkfaget i norsk grunnskole: Læreres kompetanse og valg av undervisningsinnhold i musikk. Acta Didactica Norge, 10(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.2876

- Vinge, J. (1999). Jenter, rock og den maskuline virkeligheten: En studie av et jentebands møte med rockediskursen. BLH.

- Väkevä, L., Westerlund, H., & Ilmola-Sheppard, L. (2017). Social innovations in music education: Creating institutional resilience for increasing social justice. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 16(3), 129.

- Wright, R. (2019). Envisioning real Utopias in music education: Prospects, possibilities and impediments. Music Education Research, 21(3), 217–227.

- Yang, K. (2010). Making sense of statistical methods in social research. Sage.

Fotnoter

- 1 The research project Music Teacher Education for the Future (FUTURED) is a research collaboration between Western Norway University of Applied Sciences and Oslo Metropolitan University; two of the largest providers of initial teacher education in Norway.

- 2 “GLU” is short for “grunnskolelærerutdanning”, meaning teacher education for primary and lower secondary school.

- 3 ECTS is short for European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System.

- 4 Such as medicine, law, psychology, civil engineering, economics, architecture, dentistry and so on.

- 5 Motivation can in general be defined as an interest or drive that moves individuals to do something (in this case make an educational choice) and further sustains this drive over time.

- 6 Research on student teacher motivation often categorises motivation as either altruistic, intrinsic or extrinsic (Bakar et al., 2014). Altruistic motivation mirrors the perception that teaching is an important societal profession that provides the opportunity to contribute to mastery and positive change in young people’s lives. Intrinsic motivation is about interest in the subject and the joy of the teaching profession’s tasks. Extrinsic motivation is about external conditions such as wages, holidays, stability and security (Fokkens-Bruinsma & Canrinus, 2014; Roness & Smith, 2010).

- 7 The conceptual framework in CHAT is the object-driven activity system, where subjects’ individual tool-mediated actions and individual goals are understood in relation to the context given by the rules, the community and the division of labour (Engeström, 2015).

- 8 On two occasions, the student teachers were sent a survey link via the department head, who did not want to share their email addresses.

- 9 Practicum refers to brief periods of guided and supervised classroom teaching.

- 10 Preschool, municipal schools of music and performing arts, upper secondary schools, higher education.

- 11 Choirs, brass bands, courses or by giving private music lessons.

- 12 In the Nordic countries, the terms “didactical” and “didactics” refer to the practical dimensions of pedagogy closely related to the practice of teaching a subject: the content, methods and goals of teaching (Künzli, 2000, p. 43).